Farming is usually thought of as a uniquely human invention, the story of civilization emerging from the rise of farming villages rings true in most ears that hear it. Mankind’s agency over the plants and animals we manipulate is assumed as a given in almost all discourse around agriculture. However, I recently came across a phenomenon that shattered my preconceptions of agriculture.

I was already familiar with the idea that the domestication that occurs as a result of agricultural practice is double sided. I think I first came across the idea in the book “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Noah Harari, in which he outlines among many other things, the idea that through the production of gluten and other energy dense rewards, wheat was able to piggyback off of the success of humanity and catapult itself from an obscure grass native only to a small area of the middle east to a crop that is commonly found around the globe and whose needs are met by loyal caretakers.

However, I was surprised to learn that farming has been around for much longer than humans have been participating in the practice. Enter the Leafcutter Ant.

Now you might be thinking, okay so Leafcutter Ants (also called by their more widely applying moniker “Attine Ants”) might eat plants, but that doesn’t count as farming, it’s more like gathering. And you’d be right, it is gathering.

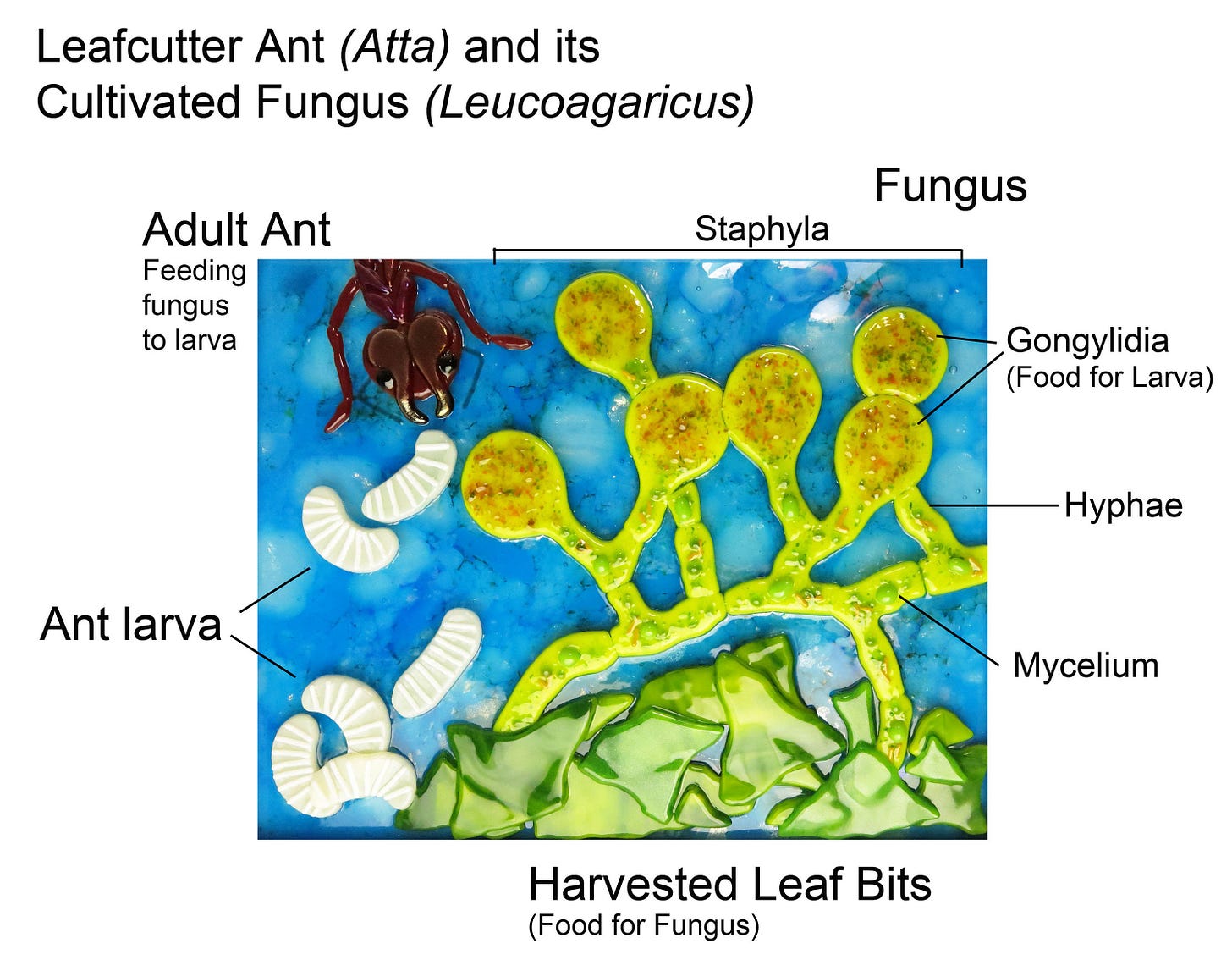

But you’d be wrong to say that they aren’t farming, because Leafcutter Ants don’t eat plant matter at all, in fact, they only eat one thing, and that’s fungus. Specifically, they only eat Leucoagaricus and very rarely (a handful of the hundreds of fungal farming leafcutter ant species) pterulaceous fungi.

In fact, the ants and the fungus that they farm are both something called an obligate symbiont, meaning that neither can survive without the other. The fungus needs the ants to supply it with plant matter, and it can’t interbreed with free living fungal varieties. It’s been fully domesticated by ants to the point where it can’t survive in the wild.

The ants need the fungus to produce a specific amino acid arginine, which is necessary for life. Their ability to produce this amino acid via their own digestion has long since withered away, and has been replaced by a dependency on the fungus.

Bacterial colonies of Enterobacter, Klebisiella, and Pantoea species play an unseen role in the relationship between the ants and their crops, acting as middle man in the digestive processes that occur within and without the bodies of the ants themselves.

So when did this phenomenon emerge? It’s thought that the first fungus farming ants came onto the scene about 51 million years ago, directly in the aftermath of the KPG mass extinction event (~66 mya) which led to significant changes in the earth’s atmosphere and climate. Importantly, the earth became much cooler, and the dust kicked up from the impact as well as volcanic activity is thought to have crippled many plant’s ability to perform photosynthesis, leading to the die off of much of the earth’s vegetation. (If you’d like to read more about this event and how it may have led to the rise of mammals, see my previous article here.)

This cool, dark, environment was perfect for fungi, who feasted on the masses of dead and decomposing plant matter. This marked the shift of the Attine ants from primarily plant based diet to one centered on fungal foods. Eventually, the ants became dependent on the fungus to produce arginine. However, the fungus was not yet domesticated to the ants. It could still survive without them and interbreed with wild varieties. We call this relationship “lower agriculture”. In a way, it would be more accurate to say that the fungus was farming the ants at this time.

The change over to mutual dependency came much later, around 33 million years ago, at the end of what is called the “Terminal Eocene Event”, where the planet once again cooled and dried significantly. This led to the expansion of the Attine ant colonies (previously bounded to the hotter and more humid biomes of South America) into drier climates. Here, the fungi could not survive outside of the gardens of the ant colony, and slowly the Attine cultivar began to become more and more distantly related to wild Leucoagaricus species until the two could no longer intermix. From here on out, the two species were dependent on one another, in a relationship biologists call obligate mutualism. In the ants, this marked the transition to “higher agriculture” and the fungus and ants began to adapt to one another. The fungus developed structures known as gongylidia, (basically like a fungal fruiting body) and the ants began to cultivate gut microbiomes that protect their crops from disease.

Leafcutter ants are now the dominant herbivore of the Neo-Tropical region, harvesting more plant matter by volume than any other organism. Although the Leafcutter Ants are essentially “locked in” to it by means of evolutionary pressure, this practice of fungal farming is also cultural in nature. When a colony gets too large, it sends out a young queen to settle a new satellite colony, and these queens take a cutting of their native home’s fungus with them to start a new garden, creating heirloom varieties of these fungi that allow researchers to trace colonial lineages.

This fascinating case-study of the Leafcutter Ant revealed to me the dual nature of agriculture as an emergent process. The reframing of our civilization’s dependency and propagation of many staple food crops as the result not solely of our will but also of the self interested genes of an organism many would consider in-animate has changed my perspective on human agricultural practices. I’d love to hear what you thought of this in the comments below.

Until next time,

-Connor, OfAllTrades

Don’t forget to subscribe, it’s free!

And please share with your friends, family, and any other prospective readers you might know!

FOOTNOTE:

A reader reached out to tell me about an interesting side effect of our relationship to crop plants, known as Vavilovian mimicry. Vavilovian mimicry is when over time, a weed comes to mimic a crop plant as a result of human driven selection effects. These weeds can become nearly indistinguishable from the species they mimic. Some even come to be domesticated crops themselves. Examples of this include the rye and oat plants, which were once just weeds growing alongside wheat and barley. This preadaptation then in turn made their adoption by humans as a crop plant much easier, and their similarities to the crops they mimic have allowed them to become crops in their own right. I found this interesting, and thought it aligned well with the idea that human agriculture is not simply a one sided affair, but that plants themselves strive to be adopted by humans for reproductive advantage. Big thanks to Nolan Monaghan for writing in!

Further Reading:

If you like reading about fungus, check out a few of my past posts on the subject!

Sources:

https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/slaves-to-wheat-how-a-grain-domesticated-us-20150718-gifbrk.html

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.150111

https://www.futurity.org/grains-food-history-globalization-1977642/

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0156847

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031018213002782

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rspb.2017.0095

http://nrm.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:719366/FULLTEXT01

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4961791/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4553616/

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s001140050777

Nice article! Even more interesting, ants also semi-domesticate other insects: protecting aphids, mealybugs or caterpillars from enemies so that they can collect the honeydew they secret. Ants not only protect their charges, but will carry them around to better feeding areas, and in the case of some caterpillars bring them into the colony nest at night to keep an eye on them.

One suspects that ants only just missed out on being the dominant species on the planet, and possibly they are in fact.

Ants are really interesting! https://dochammer.substack.com/p/ants-and-anima

Aptly timed article as I have been on a humanity's origins kick lately. It's easy to credit farming and all the downstream results as due to human ingenuity. But as you point out, it's harder to make this case in light of the example of natural farmers like the leafcutters. I wonder if we can make a principled distinction between the kind of farming human's engage in, or engaged in at the dawn of farming, and the example of leafcutter behavior. Does the question of who domesticated who even make sense or is it just an empty semantic debate?

The obvious point is that we conceptualize farming and its effects and deliberately engage in the practice. But this almost certainly wasn't the case initially. What would early farming need to look like to decide that we were domesticated by wheat rather than vice versa? I think a potentially relevant distinction is whether we deliberately engaged in proto-farming behavior, or was the success of some subset of early humans due to non-deliberate behavior that happened to enable proto-farming? Then, did the success of the proto-farmers lead to genetic adaptations for this new lifestyle? I don't know if we can recover enough information from the past to weigh in on this. Maybe the archeological record can reveal the duration of the proto-farming stage with corresponding genetic adaptations. A short duration of the proto-farming stage would suggest to me deliberate behavior. A long duration, enough for genetic adaptation, would suggest non-deliberate behavior and thus human adaptation to wheat prior to deliberate cultivation.