On April 11, 2025, the U.S. Department of the Interior issued Solicitor’s Opinion M-37085, sharply changing how the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) is enforced. In a reversal of a 2017-era policy, the federal government will no longer treat “incidental take” of 1100 species of migratory birds as a crime, and now only deliberate, intentional harm is prohibited. Essentially, this means that if a construction project accidentally disturbs some birds, that is an “incidental” taking, and will not trigger the enforcement of the MBTA.

This change is pendular a reversion to a previous interpretation, which once again undoes changes made under both Obama and Biden that had made projects liable for unintentional bird deaths. This time, the change was made under the umbrella of the Trump Admin’s EO 14154 “Unleashing American Energy” and represents a win for the abundance mindset.

How important are these bird laws? To give some context, I consult on a project that until April 11th, was required to perform a special migratory bird survey of all disturbed trees in the project area, which, if birds were found would have set back construction by two months, or necessitated that we relocate and re-nest all the birds and eggs found, which requires a special permit which is not usually granted unless the birds or human health and safety are in immediate danger. Even if a permit is granted, the process to apply and receive such permits takes several weeks. This can be a huge cost to projects.

Under the old rule, projects across the country that knew they would harm birds had to apply for special permits, which were often blocked by objections lodged by local interest groups. In 2024, the Osage nation forced a wind energy company to completely dismantle an 8400 acre windfarm which was located on land leased from private Osage members. This pattern created a cooling effect, where rather than risk any liability, developers would limit tree clearing and other activities to a 6 month “winter window”, when migratory birds are not present. Missing this window could easily delay a project by 6 months or more.

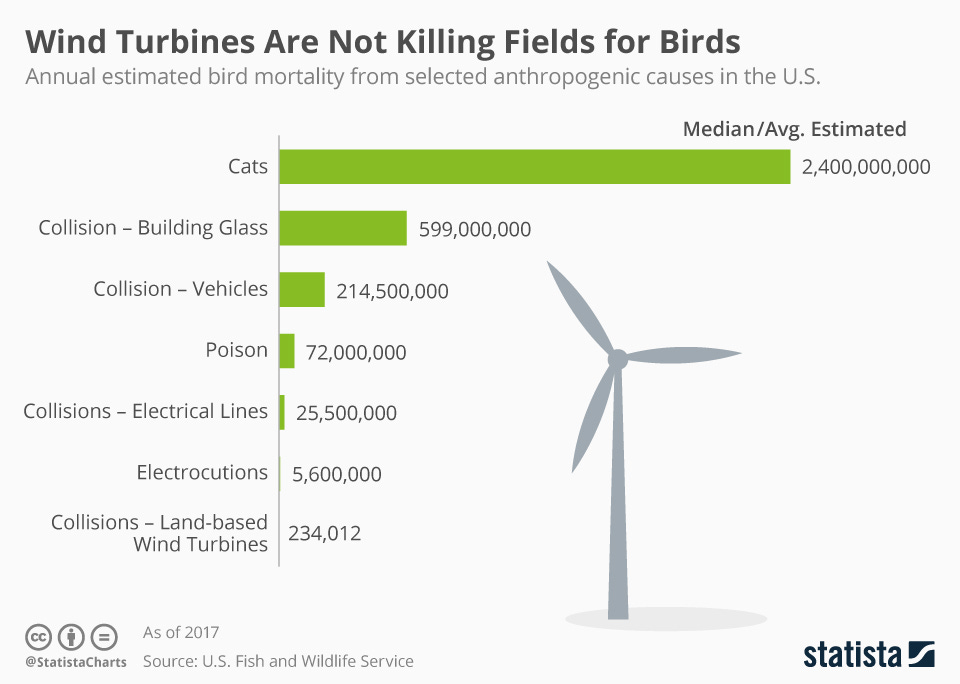

But it gets worse, under the old reading, the MBTA doesn’t just apply exclusively to projects in construction or to construction projects, it technically applies to all human activities. Enforcement was selective but still broadly impactful. In 2013 the MBTA was used to make Duke Energy criminally liable for bird deaths caused by its wind turbines. PacifiCorp once paid over $45,000 per bird killed in the routine operation of powerlines and substations! Even a building with windows that are too reflective may find itself criminally liable for bird deaths.

Broadly criminalizing incidental bird deaths essentially meant any human activity from building a house, driving a car, or even owning a cat, could be viewed as illegal, since birds collide with our structures, machines, and animals all the time. It’s a classic case of well-intentioned policy casting too wide a net. Enforcing it selectively (only some industries got hit with prosecutions) introduced uncertainty and unfairness, and smothered progress.

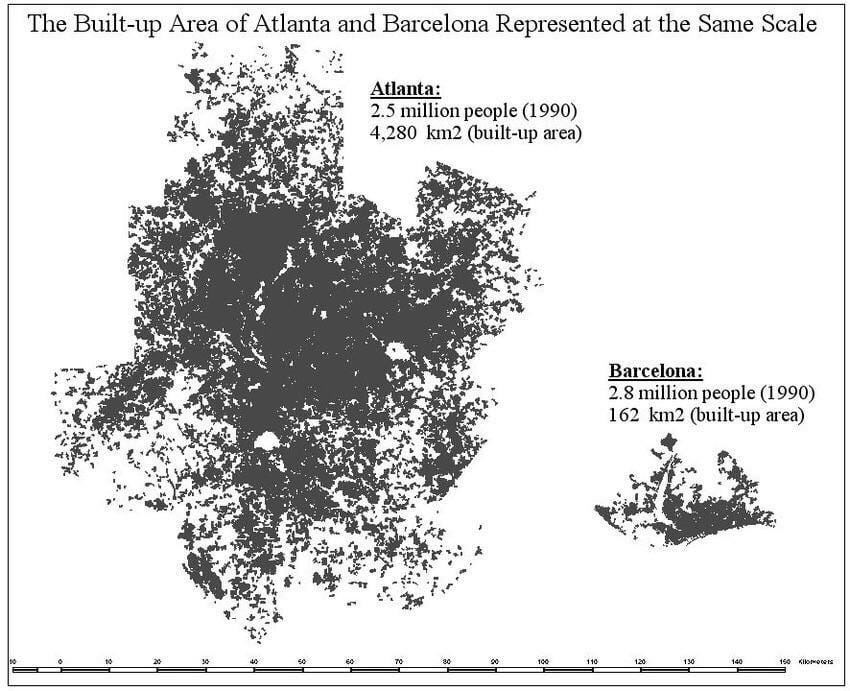

The MBTA’s incidental-take saga is a case study in the tradeoffs that paralyze today’s liberal establishments. A century-old law originally meant to stop overhunting birds was stretched to cover every incidental avian casualty of modern life, far exceeding its original scope. By refocusing the law on its core purpose (intentional harm), the government isn’t abandoning environmental stewardship; it’s acknowledging reality and priorities. This more balanced approach says: Yes, we should avoid needless wildlife harm, but we must also avoid paralyzing every construction site in the name of absolute protection. In practice, agencies can still work with developers on reasonable mitigation like bird deterrents without arbitrarily wielding the blunt instrument of criminal law to halt projects.

The next time the pendulum swings and people decry that we must “save the birds!”, we should remember that everything is a trade-off, and it behooves us to know what will be lost. We can’t build a better future if we can’t build. Speeding up construction of infrastructure and housing can benefit the environment and public well-being, even if it comes with some wildlife impacts. The abundance agenda is built on such pragmatic calculus, but dealing in absolutes is for the birds.

Thanks for reading,

-Connor, OfAllTrades