On Chinese Demography

How an empire built on a population growth Ponzi scheme has its debts coming due, and what that might mean for the Chinese people as well as the world.

In any population, there are 4 (broad strokes here) economically relevant age groups. There are retirees (65+), people in the prime of their careers, making lots of money (30-65), students, recent grads, and other borrowers like first time home buyers (16-30), and children (0-16). Based on the sizes of these groups relative to one another, an economy, and by extension the society that it serves, can change drastically. And for China, that may spell disaster.

Chances are, every graph of China you’ve ever seen has followed a familiar and miraculous hockey stick shape. China has cultivated; both at home and abroad, a reputation of non-stop growth. This perception of growth and success is often seen as the main carrot used by the CCP to quell dissent among the 1.4 billion captive constituents. The tactic is not unique to them, as the Roman phrase “bread and circuses” serves to prove. But it is concerning when juxtaposed with another key piece of information about China. A huge number of Chinese workers are about to retire all at once, and there is no one there to fill the hole. This means that in the next few years: the size of China’s retiree class will balloon, while the size of the prime earners shrinks, with the debtors and children following the same trend. One way to visualize this is with a population pyramid.

For now, lets just concentrate on the shape. Right off the bat, we can see that from the 50-54 age group on up, the populations decline with each successive year. this makes sense, because it represents people getting old and dying. The problem for China is that below that line, the pyramid pattern reverses itself, meaning that the number of working age people in China in the near future will be much lower than it is today. In fact, over the next 5 years, it’s estimated that China’s workforce will drop by 35 million, and that’s according to the CCP itself, which has been known to sweeten the statistics more than a little in the past. (see article here). The CCP says that China’s Total fertility rate is 1.6, but independent research has shown that it could be as low as 1.05, meaning that the population could almost halve in size each generation.

Here’s a gif that projects the population change to 2030:

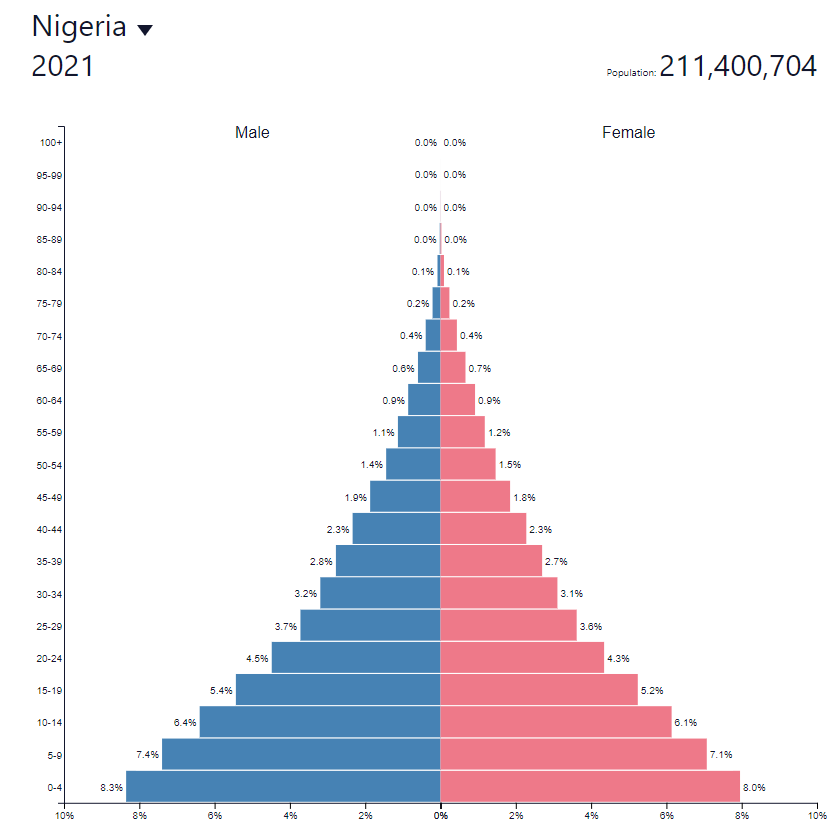

Now let’s compare the Chinese pyramid to one of a growing country, like Nigeria.

From this pattern, we can see that even the workers in Nigeria 20 years from now will have a large contingent of earners to support them when they retire at 65.

But why is this gong to be so bad for China? You may already be thinking a few steps ahead here. “Haven’t other countries experienced the same thing?” The answer is yes and no. It’s true that a similar process has been occurring in Japan, but unfortunately for China, Japan is almost 4 times wealthier than China, and their senior class had many more assets to rely on for retirement, so where Japan will have retirement-home robots, China’s elderly will likely have to live with their children. Because Japan also lacks an analog to the one-child policy, their ageing process has also been more gradual and the government has been better able to cope. This doesn’t mean they are out of the woods just yet, however, because Japan is also averse to immigration, and largely impenetrable to outsiders, so, similar to China (but to a lesser extent) they have not been able to supplement their population with immigration.

In populations like Western Europe and the U.S., growth has slowed to historic crawls, but it’s also true that places like Western Europe and the U.S. accept more immigrants than China, and broadly speaking, immigrants have lots of kids. This decline in population growth has also been much more gradual than in China, allowing for governments and markets to adapt and change alongside conditions. This means that while some ethno-nationalist’s idea of “French France” may be one whose population is shrinking, the French population is actually set to stay quite constant over the next few generations.

The reason China specifically is set to have lots of problems is 3 fold.

Firstly, China really doesn’t do immigration. What ethnic minorities that do exist within China are currently being erased, and neither the people nor the party are set on importing any new ones. To add to this, the Chinese language and culture is also very difficult for foreigners to learn and assimilate into, meaning that what few immigrants get into the country are much less likely to stay or become very productive.

Secondly, is that China has been late to admit that their population policies have been largely failures. Looking at a population graph of China shows that even the one child policy, which was long heralded as a success in reducing population growth, came after the drop in birthrate, and not before.

Let’s pause for a second to break down why the one child policy is so bad.

The one child policy is famous among groups like Amnesty International for its brutal outcomes, especially in cultures that have a strong gender preference for the sex of their child. In places like China and India, where couples are constrained in how many children they can have either by policy or by circumstance, there is a pronounced imbalance in the number of boys born compared to the number of girls. Couples put unwanted children up for adoption or abort them in black-market medical facilities to avoid prosecution. As bad as that is for the parents from a reproductive rights standpoint, what is less often talked about is what happens when these imbalanced generations grow up.

Millions of men are mathematically doomed to never marry, becoming hermited social outcasts, often burdening their own parents for years after they would traditionally have become independent heads of their own families. More than 34 million Chinese men are doomed to a sexual marketplace that they simply cannot or don’t find it worth it to compete in. These men, called “bare branches” in China, are a huge source of instability in society and surpluses of males in society, especially in China, have been shown to coincide with a great deal of revolution, violence, and unrest in the past. Today, millions flock to A.I. girlfriends to find solace in their lonely world, with one called Xiaoice claiming over 600 million unique users. When these bare branches finally snap, pent up sexual aggression could easily find outlets in nationalism, dissent, and crime.

One of the huge and understated effects of this policy is that it has now been 40 years since having one child has been established as the norm in China. All the kids who grew up as only children now only want one child in their families, creating an infertility feedback loop, which has led China to backpedal to a two, and now recently a three child policy which is said to come with more child care support programs (as of May 2021). Try as they might, the CCP’s attempts to get Chinese couples to have more kids is not going so well. With the impending costs of caring for grandma, the repeal of the one child policy did little to convince young couples to have 2 children, so experts are skeptical that the move to the three child policy will have much effect. Even if they could get couples to start having 4 kids each, those children would arrive too late to solve the impending retirement crisis. It would take about 30 years of childcare costs, education, and extra spending before they payed any significant taxes into the system.

The third reason I think that China’s demographic change presents a unique problem to them is the pace at which the problem is developing compared to the pace at which the regime is putting forth solutions. Rather than acknowledging the problem and attempting to open the country to immigrants, truly reform the Chinese language, or getting its soon to be seniors to plan a less dependent retirement, they continue to buy the compliance of the Chinese people on what is essentially credit. As growing numbers of expectant seniors burden the economy, the government will surely scramble to do everything in their power to divert the ire of the masses, who inevitably will be left with the bill.

So what does this all mean for China? Will their labor market weaken and fall into demographic collapse like Japan or do they have the resources to cope with supporting a huge and aging population? Given that Japan is much richer per capita, and is still falling deep into a debt crisis, it’s probably not a great bet that things will work out well for the Chinese economy.

Now put yourself in Xi Jinping’s shoes. At the head of the CCP, you know more than anyone that its entire existence has been built on the ability to wield the carrot of economic growth and improved standards of living, and it looks like that may be coming to an end. With no carrot left, if the masses turn against you, your only option is the stick. Better make sure that when they look for someone to blame, they find that person, elsewhere. You call up the Central Propaganda Department (yes, that is a real thing) and set them to work. “Blame everything on outsiders” you command, “oh, and while you’re at it, scrub Winnie The Pooh from all databases.”.

Jokes aside, examining the change of the official attitude of China towards the rest of the world over the past decade, a pattern emerges. In 2010, China was a country that welcomed the world into its arms, hosting the Olympic games, and building much goodwill with the outside world. In 2020, Chinese state run accounts insult foreign politicians on Twitter for points with the regime in a practice coined “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy, and are constantly spinning stories that link domestic problems to foreign entities. Prime examples include the desperate attempts to “prove” that the coronavirus originated in frozen food from outside China, and spin stories on how pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong were some sort of foreign funded insurgency. Regardless of how true these claims were, they prove a concerning pattern that China has laid bare to the world. When faced with controversy or dissent, they redirect their people’s anger outwards.

Indicative of this paranoia, the Chinese regime spends more on domestic security measures than it does on its ability to wage war, and has since 2010. The Great Firewall and the nature of the Chinese domestic Intranet means that it’s easy to stoke regime-positive nationalism within China, and historically, the pattern of ultra-nationalist movements in socio-economically tumultuous countries is not one with good outcomes for the world.

At the end of the day, I see this as essentially a powder keg problem; any way you spin it, it’ll likely be bad for the Chinese people. Economic and social turmoil are likely to follow any demographic change this big, and it seems not within anyone’s power to stop the chain reaction. Whether the regime succeeds in redirecting the inevitable backlash will determine just how far the shockwaves will reach.

-Connor, Of All Trades

If you liked this article, please subscribe!

I promise to only write about interesting things.

If you know someone who would find this interesting, please share!

Further Reading:

https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/bare-branches

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0733464819884268

Good video:

https://bit.ly/2SYrJGZ

Love the graphs, very interesting data.