Proto Pumps and Early Water Infrastructure

Different ways humanity has channeled the essential resource of water for thousands of years

Since before the first agriculturalists, civilization has depended upon water for life. Hunter gatherer tribes were bounded by where they could find and follow this precious resource, and developed canteens and water flasks to serve as a buffer for when a source was not readily available. These items were often valued more highly than a hunters spear, and were passed down multiple generations.

The first cities too, were dependent on water. Often cited as the first ever city, Çatalhöyük in modern day Turkey, was built along the Çarşamba River, and the people there had a semi agricultural diet (supplemented by hunting) that may have benefitted from the alluvial clay deposits in the area.

The dependence of farmers upon the ebbs and flows of seasonal rivers would continue on for many centuries, in the lands of Mesopotamia (which translates to “The land between the two rivers” referencing the Tigris and Euphrates rivers running through present-day Syria, Turkey, Iraq) and those of Egypt. Eventually, civilizations would come to build levees to protect their villages from the seasonal floods, and dig wells when the rivers ran dry.

All of us are probably familiar with the storied aqueducts of ancient Rome, but the history of water infrastructure is a diverse and colorful tapestry, stretching from monumental projects such as the Grand Canal in China to the waterways that crisscrossed the alluvial plains of the ancient near east. Water serves as a means of transport, a barrier to movement, and a necessity for agriculture, fishing, and people. The foundational nature of water is reflected in the amazing feats people have accomplished throughout history in it’s pursuit.

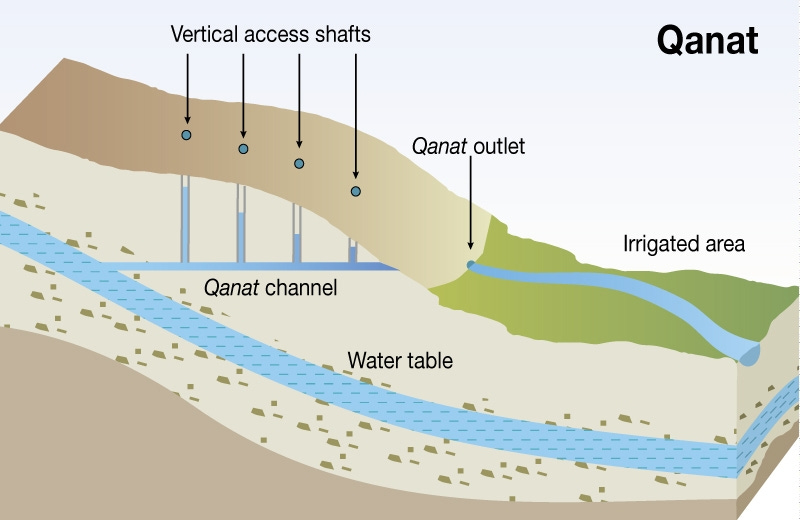

As much as 3000 years ago, ancient people’s in present day Iran dug qanats, allowing them to access and transport water from mountains and other places with a higher water table than the valleys they inhabited. These are similar to spring-fed tunnels, with the distinction that the qanat creates the mother well, which serves as an artificial spring, whereas the spring fed tunnels such as those found in Israel started with naturally occurring springs, and were simply expanded to increase flow rates. Both of these pieces of infrastructure allowed ancient peoples to irrigate their fields without depending on seasonal rains or snow melts.

Eventually though, our ambitions to channel water grew beyond even the ability to draw it from the mountains. What if we wanted to move water against the flow of gravity? A few solutions cropped up over the centuries. Of course, typical wells with buckets on ropes remained common, but vast improvements were made to this system by harnessing animal power. One example was the Cerd, in which an oxen is driven down a slope, pulling the rope of the bucket-well behind it, and drawing water from the depths below.

Also notable was the Persian well, in which oxen or slaves would turn a large wheel, whose gears would eventually serve to rotate a belt of buckets or pots, which would empty at the top into a basin or channel.

In Hellenistic Egypt, a new type of pump was developed to move water over the low lying irrigation ditches that supplied the fields along the Nile with water. Known today as Archimedes’ Screw, (Even though the device existed long before the man lived), this pump is incredibly useful, and takes advantage of water’s tendency to flow to the lowest local point by chaining together a series of low points in a spiral, which, when spun, causes the water to flow progressively up the compartments of the screw, eventually discharging at the top.

These types of pumps are still used today for drainage purposes, as they can move large amounts of water with low head. Some of the most notable examples of this being in the Netherlands, where the rotational energy from windmills is used to power similar pumps to drain polder fields.

The next device is one of my favourites. The Tympanum is a water wheel that not only produces mechanical energy as the rotation of it's shaft, but also lifts water to higher elevations. The Tympanum dates back to the Roman empire, where it was used to feed water from rivers and streams into aqueducts and cisterns. It was usually used to move water that was already running, so that it rotated without any outside energy input, but it can also be turned by man or animal power if the water is coming from a still source, such as a lake or pond. The tympanum is at it's heart is a water wheel with the paddles fully enclosed between two planes, and a hollow shaft at the middle that allows water to flow through it. As the water flows past the wheel, and the wheel turns, the curved paddles "scoop" the water out and raise it by means of rotation. Once the compartment is above the central shaft, the water then flows towards the lowest point, which is the hollow shaft, and out to whatever pipe or storage awaits it.

Some limitations of the tympanum are that it can only raise water to an elevation just under half it's total diameter, requires a running water source to power it, and cannot capture all the flow of it's source water unless it is powered by means other than flow. The tympanum was used by the romans to fill their aqueducts, and could be arranged in series such that it could drain extremely deep mines upon their flooding. This was used both in Roman Spain and in Wales, and preserved models have been recovered from the mines depths.

Similar to the tympanum, but thought to have originated as early as the 5th century BC in India, is the Noria wheel. The word "noria" comes from the Arabic term, Na-urah, meaning "the first water machine." It was the earliest mechanical device propelled by means other than man or animal. The Noria wheel is a sort of fusion between the tympanum and the bucket chain, and had the advantage of being able to raise water much higher relative to it’s diameter as compared to the tympanum. The mechanical energy of the shafts rotation could also be more easily harnessed to grind grain because unlike the tympanum, it was not hollow.

The first force pump is thought to have originated in ancient Hellenistic Egypt and was contemporary to Philo of Alexandria who authored Manuscripts of Pneumatica, dating it to somewhere around 25 B.C.. Shown above is an idealized diagram of the force pumps found across the late Roman Empire. As it was a mainstay of the late roman empire, it was probably operated by slaves, which in the later centuries of the empire, made up nearly 30% of the empire’s populace.

The last piece of water infrastructure I’ll cover is something I’ve had the pleasure of seeing in person, the stepwell.

The earliest stepwell probably emerged in India somewhere around 200-400 AD. Stepwells allow access to key water resources that would otherwise be locked deep below the surface. They also served as cool retreats for people to flock to on hot days, often maintaining temperatures as much as 6 degrees C below their surroundings. Stepwells are some of the most visually stunning pieces of water infrastructure I’ve come across, and serve as monuments to the importance of water in our lives and history.

By surveying the solutions of our ancestors from the aqueducts of Rome to the first pumps, we can draw important parallels to current problems, and seek new insights that may light the path to a better future. I hope the article gave a sense of scale to the historical context of work done by contemporary water resources professionals. For thousands of years, water infrastructure has been a diverse and innovative field, with far reaching impact, and is too often taken for granted.

Until next time,

-Connor, OfAllTrades

NOTE: An abridged version of this post was published in the Texas American Water Works Association’s H2O magazine, and can be accessed here.

And please share with your friends, family, and any other prospective readers you might know!

And if any of you readers out there are secretly crypto millionaires and would like to leave a tip, please check out https://alltrades.eth.xyz/

Wonderful. Many thanks!

Very interesting...