The Texas M.U.D. Model

How Special Districts Paved the Way for Housing Abundance in Texas Cities

Texas has developed a reputation for fast-growing cities with relatively affordable housing. On this graph (from

) the four major cities of Texas stand out as some of the only major metros in the U.S. occupying the graph’s lower right quadrant. Why is it that housing abundance is a Texas exclusive phenomenon?One key reason is a novel approach to financing and governance at the suburban fringe: the Municipal Utility District (M.U.D.) model. These special-purpose districts let developers create new communities from scratch by funding infrastructure with *future* residents’ taxes, effectively building whole neighborhoods on “spec” without burdening existing city budgets.

In this post, we’ll dive into the origins of MUDs in Texas, understand how they work technically and financially, and why they’ve become a cornerstone of the state’s pro-growth, pro-housing environment.

Origin Story: How MUDs came to be

The idea of special districts isn’t new in Texas – the state has used independent local districts sine the 1890s to tackle water, irrigation, and flood control needs. Early on, Texas amended its constitution (Article XVI, Section 59 in 1917) to empower water districts with taxing and bonding authority, seeing them as tools for developing arid lands. Their status as “subdivisions of the state” has played a key role in how they have driven development in more recent times.

In the mid-20th century, developers began using these districts for suburban residential projects, especially as cities struggled to extend utilities to far-flung areas. Some of the first MUDs used for this purpose were in Houston in the 1960s and 1970s. Houston’s explosive growth (fueled by the oil boom) quickly outpaced the city’s own infrastructure expansion, so developers turned to MUDs as a solution.

Throughout the 1970s, master-planned suburban communities like The Woodlands, Clear Lake City and Sugar Land’s First Colony sprouted on former fields, enabled by MUD-financed water and sewer systems. These communities measure in the tens of thousands of acres, and house hundreds of thousands of people.

By the 1980s, the MUD model had caught on widely: development “leap-frogged” beyond Houston’s city limits into unincorporated areas, all serviced by these autonomous districts. Developers in other fast-growing Texas metros caught on, and soon the MUD model (as well as other special district models) spread to Dallas-Fort Worth, Austin, San Antonio, though Houston remains the epicenter.

The MUDslide

Why did the MUDs catch on and spread so quickly among developers in Texas? A few things about Texas made it conditions ripe for MUDs to rise:

1.) Weak Texas County Governments:

Texas counties have limited authority and revenue for utilities or roads in unincorporated areas. This creates a vacuum at the edge of growing markets which attracted developer interest.

2.) Low Appetite for Risk within Municipal ETJs: State law gives cities an “extraterritorial jurisdiction” (ETJ) ring outside their boundaries, but cities often *declined to extend utilities* into these areas due to cost or risk. Existing citizens didn’t want to pay for infrastructure to support new transplants. MUDs allowed development in the ETJ without immediate city annexation, solving the infrastructure gap.

3.) Conditions were right for independent infrastructure. Around Houston and Austin, large tracts of undeveloped land lay just outside city limits, often with accessible groundwater for wells. This made it feasible for new districts to supply water independently and build entire communities on what had previously been empty prairie or ranch land.

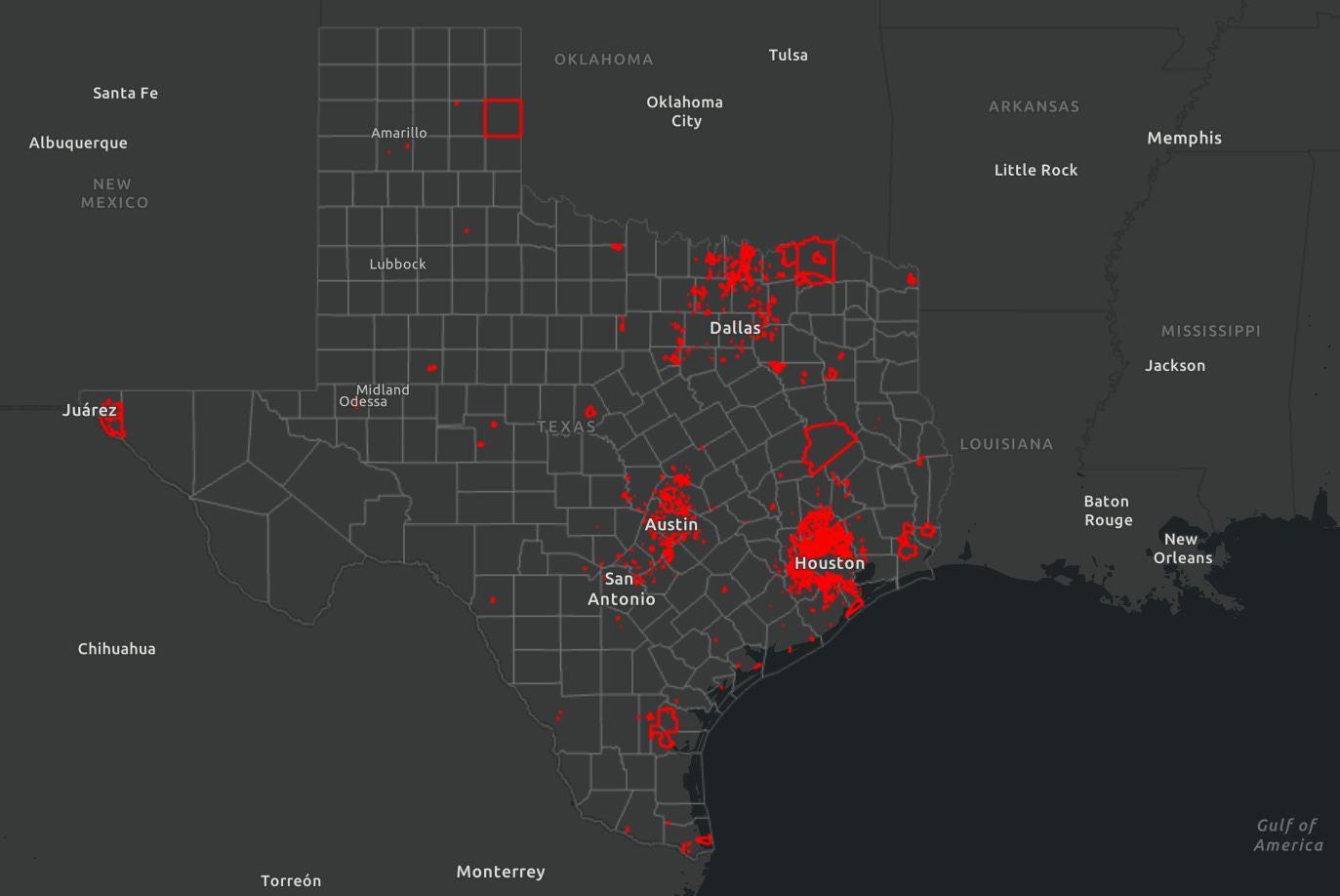

This mix led to the state of MUDs in Texas today. Over 950 Texas MUDs currently exist, and as development continues, even more may arise. But as the annexation map above shows, MUDs aren’t necessarily permanent, and many eventually get annexed by the local municipalities. Texas cities frequently annex developed MUD areas decades after growth occurs (Houston annexed Kingwood, Clear Lake, etc.), but notably MUDs enabled the growth to happen in the first place: growth that might never have occurred if it had waited on city financing or approval.

MUD Financing, How Does it Work?

At its core, a Municipal Utility District is a small government entity created to fund and provide basic infrastructure in an area where city services don’t exist. The genius of the model is how these services are financed: developers front the costs, and *future* homeowners repay those costs over time via property taxes and utility fees. Here’s how a typical Texas MUD comes to life:

Step 1 - District Creation

A developer or landowner with a large parcel (often empty land) petitions the state to create a new MUD for that area. This petition either goes through a special law passed by the Texas Legislature or to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). If a MUD is within an ETJ, they have to agree to let the MUD take it, and usually do so with some standards to which the infrastructure should be built, expecting to annex the MUD in the future.

Once you get permission, you can get to founding your MUD. This can be done with as few as two people as residents to form the board. In one case, a Houston-area MUD was created after a developer arranged for two people to live in a trailer on the property and hold a 2–0 vote approving the district and $188 million in bond authority. This establishes the MUD as a legitimate elected body over the area.

Step 2 - Build, Baby, Build!

Now that the MUD is founded, the developer builds out the infrastructure. They build water lines and sewer systems (often drilling wells and erecting treatment plants if not connecting to a city), drainage ponds, streets and sidewalks, fire stations, street lights, and sometimes parks and playgrounds. All of this is done with the developer’s own capital or private financing. Essentially, the developer is acting like the “city,” constructing the backbone that homeowners need. This can require tens of millions of dollars for a large subdivision. Why would a developer take on these costs? Because the payoff comes next: the MUD will reimburse the developer by issuing tax-exempt bonds after enough homes are built.

Step 3 - Sell em like hotcakes!

Now that they’ve spent big on the infrastructure, the developer is in a race to build and sell as many homes as they can in as short of a time period as possible. Remember, all of the money they’ve spent so far is from their own pocket, or loaned to them at interest! The MUD helps the developer sell these homes with a low sticker price, because the cost of the infrastructure supporting them is not included in the home price, but rather will be collected by the MUD via it’s authority to tax residents. TCEQ has guidelines that say that a MUD can’t issue any bonds until 25% of the value of planned homes has been built and assessed. They also have to show that the tax burden on future residents is reasonable, which usually is achieved at around the 40% occupancy rate.

Step 4 - Collect!

After meeting the requirements and getting approval from TCEQ and the Texas Attorney General, the MUD will issue municipal bonds on the public market to raise funds. These bonds are backed by the MUDs right to tax residents and are therefore quite a safe investment, they are also tax-free! So lots of people buy these bonds, and the money goes to reimburse the developer for fronting the capital in the first place. By paying out on the bonds, new homeowners gradually pay off the infrastructure over 20–30 years instead of having those costs loaded into the upfront price of the home. Once the bonds are paid out, the tax rate generally drops to cover maintenance costs. As the MUD matures, they are required to elect real residents to run the district. A MUD will continue to exist until and unless the city annexes the area and takes over services and the MUD is dissolved. In the Houston area, annexation was once common, but in recent decades cities have slowed annexations, meaning many MUDs persist as permanent local governments run by the residents.

In summary, the MUD model aligns the timing of costs and benefits: developers build first, get paid later; homeowners buy homes, pay later for the infrastructure through taxes; and cities get growth without upfront expense or risk. It’s a clever public-private partnership that became a standard operating procedure for Texas suburbs. It reminds me of

and discussions of the tradeoff between present and future people. In the case of the MUD, it seems to be a viable way to borrow from the future, *because* the future people we borrow from benefit too.Where are all the MUDs?

MUDs have parallels in other states. Let’s start with the states that build.

Florida has Community Development Districts, which are a lot like MUDs, with the main difference being that Texas MUDs are more vertically integrated, while Florida CDDs don’t usually operate the infrastructure they finance. Colorado has metro districts, which operate like MUDs but get permission from local cities rather than the state legislature or from a TCEQ equivalent.

It’s no coincidence to me that these states also lead in championing new growth (see Denver, Orlando, and Tampa on the graph, some interesting data here too).

Some cooling forces may be too great for MUDs to overcome, as in the case of California. California has something caled the Mello-Roos Community Facilities District law (since 1982), which allows a city or county to create a special district to finance infrastructure with voter-approved special taxes. In practice, many new subdivisions in California do have Mello-Roos taxes that homeowners pay for 20-40 years to fund roads, schools, etc. The difference is that these CFDs are usually initiated by local governments and don’t create a separate governing board the way MUDs do; they are more a funding mechanism than an independent mini-government.

California’s governance and environmental regulations (like CEQA) also mean that even if financing is available, getting permission to build large new communities is very difficult. So, while California has the legal ability to do something MUD-like, the broader land-use climate has limited its impact. One could imagine, however, that if California reformed some of its processes, it could empower private developers to form their own utility districts in peripheral areas to jump-start housing through a more autonomous version of CFDs. This might help build new towns in the Inland Empire or Central Valley to take pressure off coastal metros.

By contrasting California and Texas/Florida, we can take away that MUD’s are a helpful but not sufficient ingredient in the recipe for affordable new development.

When MUDs get dirty

There are a few concerns when it comes to the MUD model. Everything comes with trade-offs and MUDs are no different. While MUDs have clearly facilitated growth, they are not without downsides even from a pro-growth perspective. Here are some of the key concerns and how Texas has addressed them:

1.) MUDs Facilitate Sprawl:

This is a common objection to MUDs from the optimal urbanism camp. It’s true that most MUDs are suburban in character (single-family subdivisions with cul-de-sacs and lawns). If one’s goal is dense urbanism, MUDs might seem counterproductive. However, nothing in law limits MUDs to sprawl; they simply finance infrastructure, and could just as easily fund an apartment grid or transit-oriented development if a developer chose that. In fact, some MUDs around Houston have begun incorporating mixed-use “town center” projects within them.

2.) Are MUDS a good deal?

Critics also point out that by the time the 30-year bonds are paid off, homeowners may have paid more in taxes plus interest than the original infrastructure cost. It’s akin to a mortgage on the neighborhood’s roads and pipes. But that’s the cost of borrowing: residents get the benefit of living in a fully serviced community during those years. It’s also worth noting that a MUD board composed of residents can choose to prepay or refinance bonds if advantageous, just as a city might, or use any surplus from growth to pay debt down faster. Many older MUDs in Texas have indeed paid off bonds and reduced taxes substantially over time. Without MUDs, there may have never been homes for these people to buy in the first place!

3.) Infrastructural Balkanization

A mosaic framework of MUDs doesn’t always appeal to central planning minded folks, and it can be hard to coordinate and solve problems of common resources. Usually, cities can help to standardize MUD infrastructure by requiring that the MUDs build to their code when consenting that the MUD take land out of the municipal ETJ. MUDs outside of ETJs, while not beholden to city standards, still need to meet state design code, but have the freedom to operate as infrastructure laboratories, fueling innovation and efficiency for all future builders.

For example of a coordination problem, widespread groundwater pumping by dozens of MUDs in the Houston region led to aquifer depletion and land subsidence (ground sinking, read more on settlement and subsidence in my past post here) in past decades. The solution was the creation of regional water authorities that forced coordination across MUD boundaries.

4.) Governance and Accountability

The democratic deficit in early MUD formation raises eyebrows. As noted, some MUDs are created with just a handful of proxy voters approving huge bond issuances. This can lead to conflicts of interest. For example, a developer-controlled board could approve buying infrastructure from the developer at inflated prices, or hiring the developer’s affiliates as contractors.

Additionally, once residents take over, they are essentially managing what can be a complex utility business without the resources of a full city government. A small MUD board might lack professional oversight compared to a city council. These issues have occasionally led to mismanagement and corruption.

However, Texas provides some checks: MUD financials are subject to review by state agencies and required annual audits, and any new bond issues or tax increases are generally transparent to voters. The initial developer-appointed board is temporary, so within a few years, residents get to elect their board and can kick out any bad actors. In practice, many MUD boards hire reputable outside consultants (like yours truly) to advise them, and there’s a whole ecosystem of professional firms in Texas that specialize in running MUD services efficiently.

The sheer number of MUDs (nearly a thousand!) means oversight is decentralized and some will be better run than others. But from a pro-growth view, this light oversight is part of why MUDs are nimble, and the drawbacks to local governance are not unique to MUDs.

MUDs - fertile ground for abundant growth

Naturally, MUDs are not a panacea for every housing issue. They primarily address greenfield development (or large brownfield redevelopment) – they won’t fix zoning limits in fully built cities or substitute for infill where that’s needed. And they require that there is land available to develop (Texas had plenty of cheap land around its cities, which isn’t the case everywhere). But as one tool among many, the MUD model could significantly expand the housing frontier in states that have hit a wall with traditional development processes. MUDs are a hammer, and new housing isn’t built entirely from nails.

Texas’s Municipal Utility District model demonstrates how empowering developers to build infrastructure (with oversight and the promise of future repayment by residents) can create a virtuous cycle of growth. It aligns incentives for pro-housing outcomes: developers build, investors buy bonds, families get new homes, and cities ultimately gain thriving communities. The historical success in Texas (despite some bumps) suggests that other regions grappling with housing shortages might do well to study the MUD playbook.

The overarching lesson policy makers should take from Texas is that when you remove upfront barriers and spread costs over time, you can unleash development on a grand scale, to the benefit of millions of would-be homeowners.

Thanks for reading!

-Connor, OfAllTrades.

Like this article? Please Subscribe!

Know someone who would? Please Share!

Could you share the source for the title graph? Super interesting but axes ambiguous (nominal or inflation adjusted, and is growth annualized) and I'd be interested in seeing source data. 20%+ annualized growth rate for 8 years is over 4x is implausible, but it's definitely not cumulative growth https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austin,_Texas