The Spice Must Flow: The Dutch-Portuguese War-Part 2

As flames rise across the globe, a new Dutch Empire, forged in the fire of war, rises from the ashes.

In the first post in this series, we took a look at the Dutch-Portuguese War, diving into the background for the conflict, the motivations of the belligerents, and the strategy and key battles of the Indian Ocean theatre. This time, we’ll examine the fighting in the Americas and Africa, and characterize the importance of the war as a battle not only between fleets and armies, but also of behemoth ideas and institutions that would come to shape our modern world.

BACKGROUND

In contrast to the Indian Ocean Theatre, the Atlantic Theatre of the Dutch-Portuguese war saw a much more even balance emerge between the Portuguese and their allies and the Dutch West Indies Company (W.I.C.). This was in no small part due to the greater Spanish presence in the theatre, but also had to do with the difference in nature of the Iberian holdings in the Atlantic vs. Indian Ocean Theatres. In the Atlantic, the Iberian forces often had a deep frontier of friendly and self sufficient settlements to retreat into, licking their wounds and recovering their strength, whereas the Indian Ocean was a landscape dotted with outposts that were often isolated from any possible relief or reinforcement (other than by sea). Due to this contrast, Dutch victories in the Atlantic were in many cases closely followed by Portuguese recovery.

Additionally, Spanish treasure ships were less vulnerable to privateering, due to their more extensive use of convoys (called flotas), as compared to the Portuguese. Instead of isolated Portuguese galleons laden with sugar and slaves, privateers looking for a Spanish meal faced a daunting treasure fleet, with escorts ships armed to the teeth.

However, even when the chips fell back into their original positions, the effect of the conflict in weakening Iberian entrenchment in the hemisphere is important and often understated, as it lowered the barrier to entry for other outside powers to enter the fray.

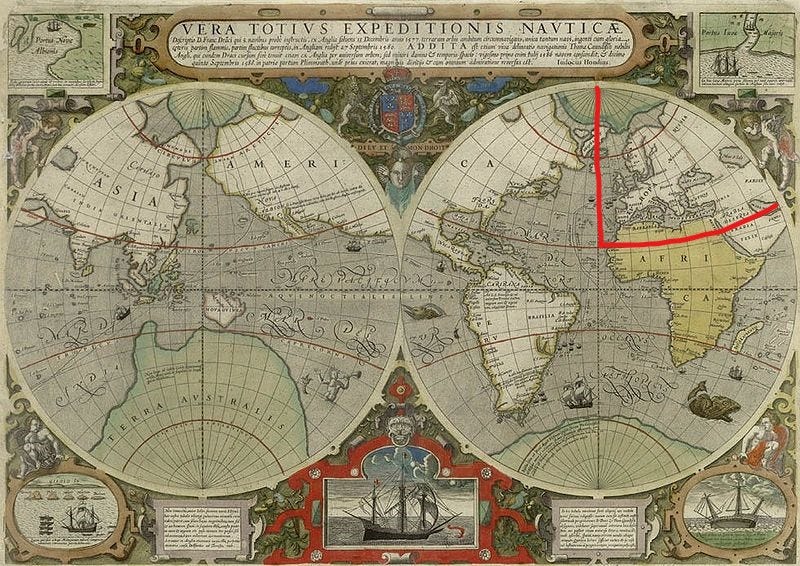

What exactly were the Dutch aiming to accomplish in the theatre? Enter the Groot Desseyn (Grand Design) of the W.I.C., which hinged on seizing key ports and disrupting Iberian shipping, to starve the treasuries of Spain and Portugal, and hopefully grinding their war efforts to a halt.

In the Groot Desseyn, the Dutch would seek to first capture Salvador de Bahia in Brazil, which controlled entrance to the Bay of All Saints and Paraguacu river, and was an important port of entry for ships and goods coming from Africa. Then, the plan was to jaunt over to the African Coast to strike the relatively weak fortress at Luanda, and travel up the African coast to assault the now isolated fortress of Elmina in West Africa, which was initially avoided due to it’s defensiveness.

AFRICA

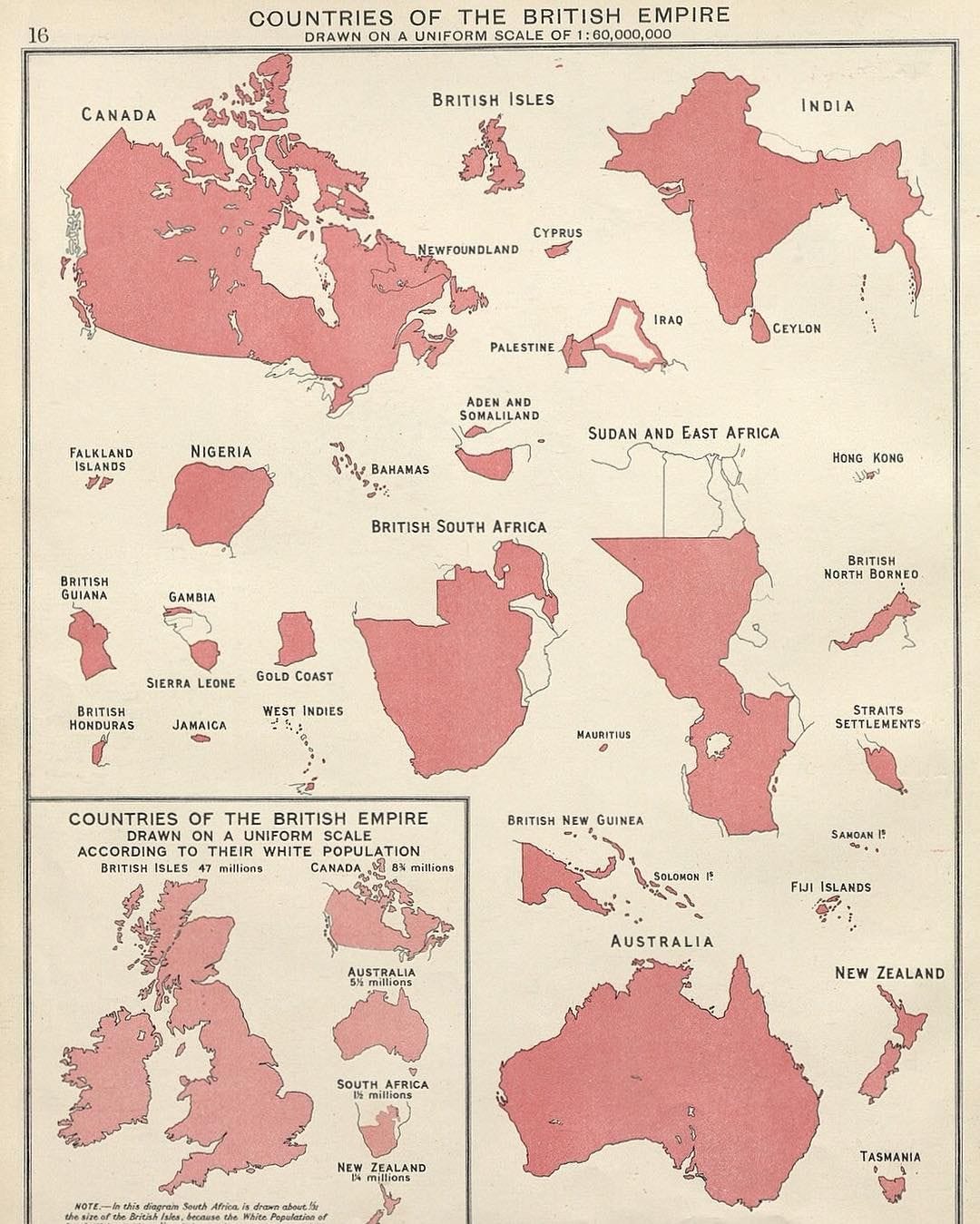

The Atlantic African coast was coveted by European powers in the 16th and 17th century for it’s key role in control of the slave and triangle trades. Over the course of the war, the Dutch West Indies Company would seize Portuguese colonies and trading posts in the Gold Coast and the Congo areas, and involve themselves in local politics and affairs as traders in many other West African periphery areas.

The Dutch would hold their Gold Coast colony until 1872, when they sold it under duress to the British for 46,939.62 Dutch guilders, (only about $2M today, converting from guilders to gold to dollars)

The Dutch victories in the Congo and Angola would prove more temporary. Soon after the capture of the area by a Dutch fleet fresh from a victory in Brazil, and it’s incorporation into the W.I.C., the Dutch found themselves embroiled in local affairs, and they were unable to cement their control over the region.

The Dutch Cape Colony was a late addition in the span of the war, only being settled in 1652, just 11 years before the end of the war, but would go on to play a large role in the shipping and extraction of natural resources from the Indian Ocean and African theatres, and as a key chokepoint, cemented the Dutch ability to trade between the Indian Ocean and European ports.

THE CARRIBEAN AND AMERICAN THEATRES

Lets take a closer look at the American/Caribbean theatres, and some key differences to those of Asia and Africa that allowed the Iberian powers to more effectively combat Dutch attempts to undermine their presence in the theatre.

1.) As we touched on earlier, Iberian holdings here had the advantage of retreat, and could not be defeated in detail as easily as the isolated holdings in Africa and Asia. When the Iberians lost here, they often faded into the countryside to lick their wounds, and draw from the colonial reservoir of money, men, and materiel to mount counter-attacks. This largely contrasts with how things played out in Africa and Asia, where isolated garrisons and fortresses could be taken in sequence from the periphery inward. These forces, which often had fewer options for retreat, were more likely to formally surrender, granting the Dutch cheaper victories with more staying power.

2.) The goods traded by the Portuguese and Spanish in the Atlantic during this time were different in a few key ways. The Spanish goods (especially precious metals and porcelain) could be temporized, meaning that they could be stored with minimal losses to degradation, while Portuguese goods (Largely slaves and sugar) were much more volatile. This led to a difference in fleet size! Portuguese ships in the Atlantic were constantly making the journey back and forth between Brazil and Africa due to the perishable nature of the goods they traded in, while Iberian ships returning to Europe from the colonies (Mostly Spanish) made the trip much less frequently, in large convoys called flotas. The Spanish treasure convoys, while they were huge targets, were easier to protect from privateers than the smaller Portuguese groups of ships and their escorts, which could be targeted by smaller privateering fleets at a lower risk.

Quantifying the degree to which piracy occurred in the Ameri-Carib theatre is difficult due to the asymmetric nature of the practice. Because of the Spanish and Portuguese policies of Mare Clausum (discussed in part 1), any foreign ship travelling through the waters claimed by Iberian sovereigns without paying for passage or trading rights, could be considered to be engaging in smuggling, piracy or otherwise prosecuted harshly. Successful pirates were notoriously secretive about who and what they captured. Rather than ransom their prisoners, they often sold them into slavery instead.

I’d love to see some analysis on the economic history of pirates and privateers and their impact on trade, if you know of work in this area, please leave a comment! All I could find was studies on Somali piracy and some work on the organizational structure of pirate ships, but few estimates of the total booty taken. Perhaps I would follow the breadcrumbs from the foundation of Lloyd’s of London, which started as a maritime insurance underwriter in 1689.

HAVANA AND THE SPANISH MAIN

There were some daring strikes on treasure fleets over the course of the conflict. Predated by some more minor French and English captures of Spanish ships; the capture of an entire Spanish treasure fleet in September 1628 likely takes the cake as the biggest prize. The Dutch force of 31 ships led by Admiral Piet Pieterszoon Hein (with the help of a pirate!) captured the entire New Spain treasure fleet on its way to Havana. The Dutch seized 46 tons of silver and many other valuables, (worth over 11 million 1628 guilders, or about 350m 2021 euros) in the raid, which nearly bankrupted the Spanish empire. However, they were unable to seriously threaten the fortified ports of the Spanish Caribbean, and so returned home laden with booty. Shareholders in the Dutch West India Company received 50% cash dividends that year.

Admiral Piet was the only privateer to ever capture a large part of the Spanish Treasure fleets. He famously also captured 30 Portuguese ships in his 1627 series of raids on the port of Salvador in Portuguese Brazil. He would die guns blazing in 1629, heroically sailing his ship in between two enemy ships to give them simultaneous broadside fire.

THE BATTLE FOR BRAZIL

As part of the Groot Desseyn, the Dutch West India Company turned their ambitions to Portugal's massive colony in Brazil. In 1624, a WIC fleet of 51 ships carried over 3,000 soldiers in an audacious strike against the city of Salvador (now the capital of Bahia state). Catching the Portuguese garrison unprepared, the Dutch overwhelmed the defenses and occupied Salvador for over a year.

Though eventually repulsed, the Dutch persisted, returning in 1630 to seize the northeastern captaincies of Pernambuco, Itamaracá, Paraíba, and Rio Grande do Norte. They consolidated their Brazilian territories into the colony of New Holland, governing from the capital of Mauritsstad (present-day Recife).

For the next quarter century, Dutch settlers, Jewish immigrants, and African slaves poured into this corner of Brazil. Mills processed the region's bountiful sugar harvests, while the WIC waged a seesaw battle with Portuguese forces over the colony's future. Ultimately outnumbered, the Dutch finally abandoned their Brazilian foothold in 1654 after over 30 years of occupation. In the Treaty of the Hague, which is widely accepted as the official end of the war, the Dutch renounced their claim to the area and ceded it to the Portuguese, for 63 tonnes of gold.

OUTCOME AND IMPACT

At the end of the conflict, the Netherlands were free from the Catholic control of the Spanish Habsburgs, the Portuguese had lost control of the most lucrative of their trading posts in the Indian Ocean, and cracks were beginning to show in the Iberian stranglehold on trade in the Atlantic. The capitalists of Northern Europe bayed like hungry dogs at the wounded lion of the Iberian Union.

Religiously, the Dutch-Portuguese War can be seen as part of the broader conflict between Protestantism and Catholicism that defined much of European politics at the time. The Dutch Republic, having declared independence from Catholic Spain in 1581, was predominantly Protestant, but still tolerated Catholicism among the citizenry. This fight for independence against the Catholic Spanish Habsburgs extended naturally into a conflict with Portugal, which was in a dynastic union with Spain from the 1580s to 1640s. The Dutch sought not only to undermine Catholic hegemony but also to establish themselves as a Protestant maritime power. The inclusive markets and institutions of the Low Countries, forged in the fires of conflict between Catholics and Protestants, attracted much human capital, not only from Christendom, but also from other faiths. Leveraging this human capital would allow the Dutch to supercharge their economy and industry, catapulting them to wealth and power.

Socially, the war also represented a shift of financial power from the colonial empires in Iberia to those emerging in Northern Europe. Many Jewish families in the Iberian Peninsula had faced persecution under the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions. A significant number of Jewish refugees, fled to the more tolerant Dutch Republic, where they could practice their faith freely. They brought much wealth, expertise, and knowledge of trading routes with them. Some estimate that Jewish traders may have made up as many as 1/3rd of all merchants in Portugal before the Portuguese began to persecute them (beginning in 1547, but intensifying after Portugal fell under union with Spain).

The Sephardim (Iberian Jews) had a distinct advantage in the trade of sugar, leveraging their post-diaspora network of knowledgeable merchants to play a pivotal role in the transatlantic sugar trade. The Sephardim would become the dominant importers of sugar to Amsterdam (where religious tolerance allowed them to flourish) in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At one point, they threatened to take their business elsewhere if Dutch authorities did not hand over captured stocks of sugar, and even petitioned the Dutch government to grant them a monopoly on sugar trade with Brazil, on the grounds that they stimulated the local economy. You can read more about their involvement in Atlantic trade here.

Economically, the war represented a clash between emerging capitalist principles, embodied by the Dutch and their open institutions, and contrasted by the traditional colonial empires of Spain and Portugal. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (WIC) were pioneering capitalist enterprises that used private investment and advanced logistics to dominate trade routes and exploit resources. These gains were not simply made property of a king or dynasty, but were distributed as incentives to those who made them. Here are graphs of their stock prices, which often paid large dividends to holders.

By expanding private capital's role and minimizing rigid state control, the more dynamic and profit-driven Dutch system progressively displaced Portuguese imperial mercantilism as a trade/colonial model over the following centuries. The Dutch Groot Desseyn, although not completely successful, disrupted the Iberian control of critical trade routes and resources, such as spices from India and sugar from Brazil, and opened investment in such plays for power to the merchant classes, fundamentally altering the structure of global trade.

This ideological conflict's outcome had dramatic repercussions in shaping the modern international economic order. Many other Northern European countries took notice of the blow dealt to Iberian power in the world and hungrily eyed their possessions as they adopted bits and pieces of Dutch strategy.

In many places, the Dutch were made to give way to the British, but their model of free(er) trade and merchant autonomy would echo through history as one of the first drumbeats of modern capitalism to be heard above the cacophony of colonialism and conquest. Although empires would continue to span the globe for centuries to come, they would no longer be heard as single voices, but rather great choirs, with melodies of trade, finance, and freedom harmonizing together to weave the song of power.

Thank you for reading.

-Connor, OfAllTrades.