Venice, the city that “floats on water”, has faced a huge challenge since its founding- Where does a city surrounded by saltwater get freshwater?

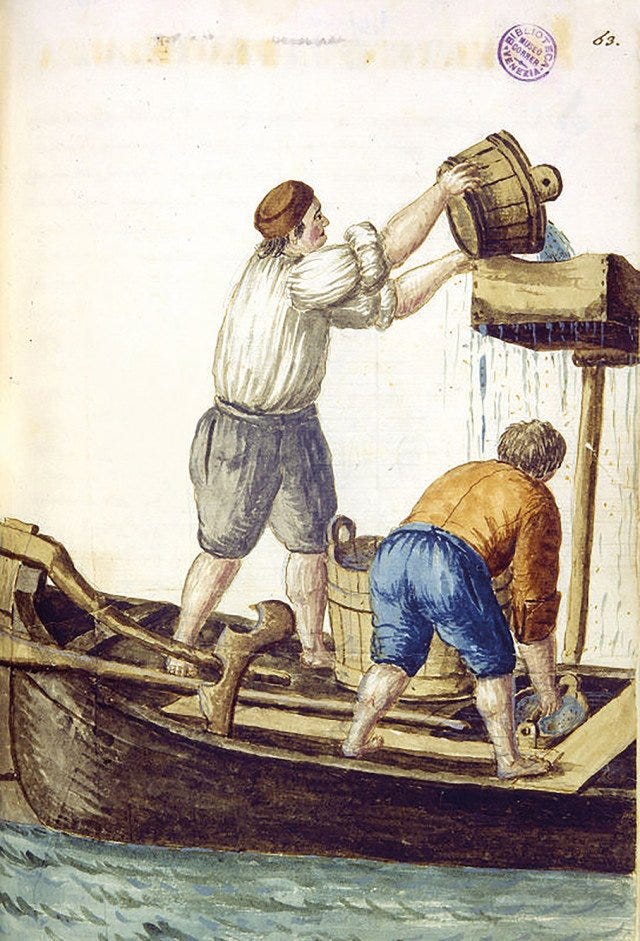

Unlike most medieval cities that could simply dig down to access groundwater, Venice's unique position atop mudflats in a brackish lagoon required remarkable engineering innovation. The muddy soil made the walls of excavated areas extremely unstable and prone to collapse, further disqualifying the city from using conventional wells. Importing water from the mainland, either by means of an aqueduct or water-boats, left the small merchant republic vulnerable to siege by land-based powers.

To solve this problem and maintain their independence, the ingenious residents developed a system of rainwater collection cisterns and wells that would help sustain the maritime republic for centuries.

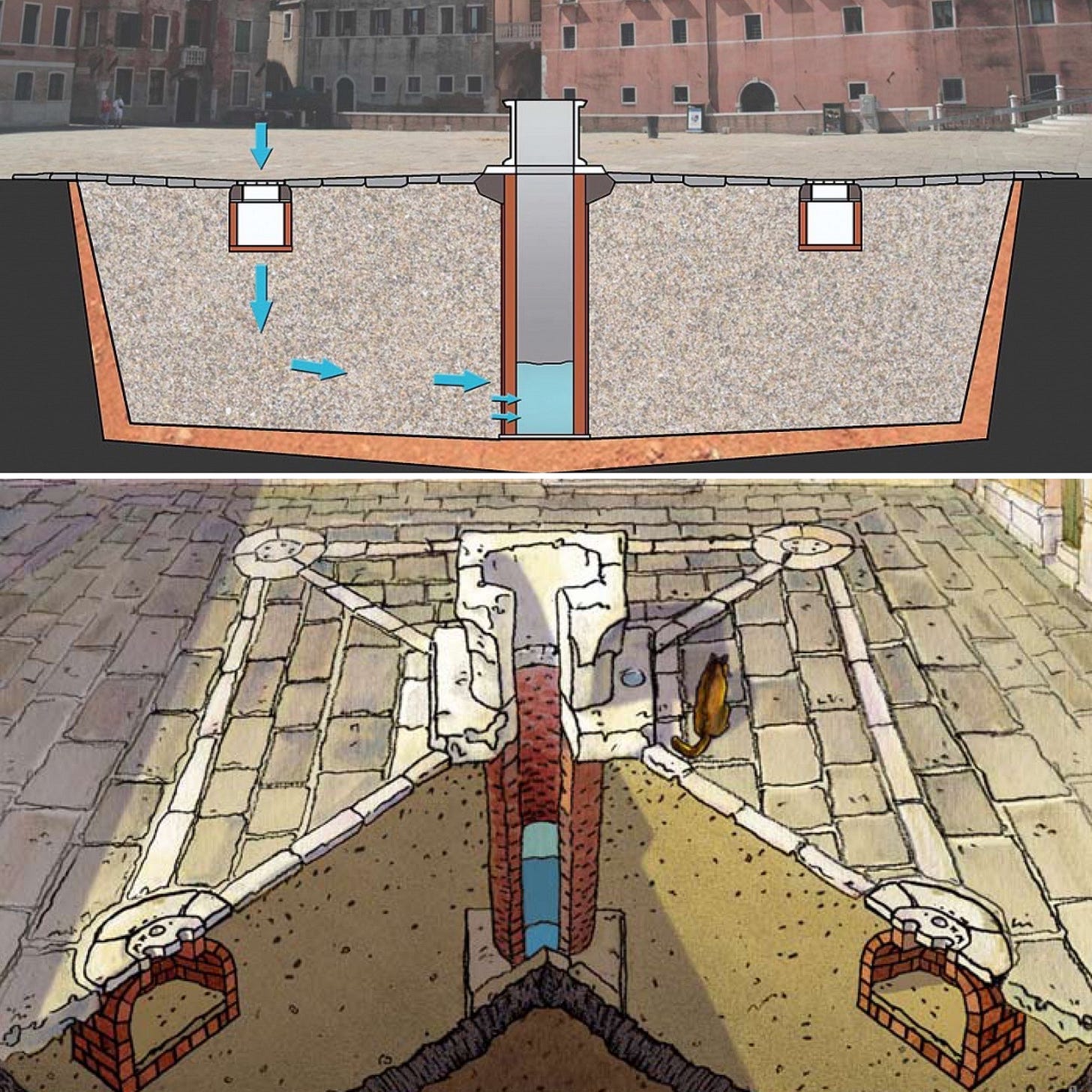

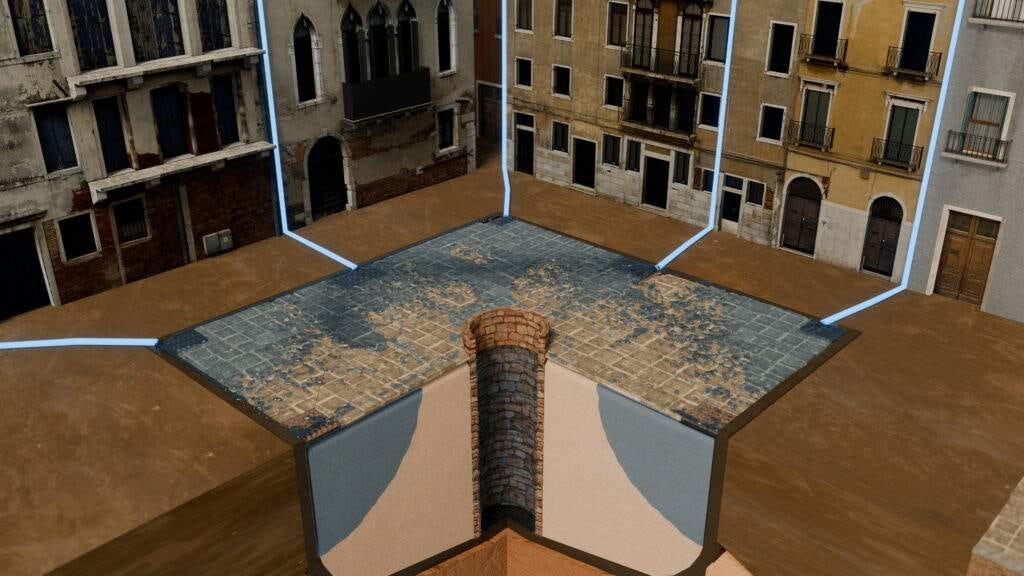

At first glance, these wells appear similar to those found in any medieval European city - cylindrical stone structures with ornate wellheads rising from squares and courtyards. But beneath the surface lies an engineering marvel that showcases Venetian ingenuity.

The typical Venetian well wasn't actually a well in the traditional sense - it was closer to a sophisticated cistern system. Here's how it worked:

The pavers in each courtyard were subtly sloped to direct rainwater toward the well inlets, called casselle

Below ground, a large inverted bell-shaped chamber was constructed, lined with waterproof clay

The chamber was filled with layers of sand acting as a natural filtration system

Four to eight stone casselle around the well's perimeter collected and channeled rainwater into the sand

The filtered water would collect at the bottom of the chamber, accessible through the wellhead

The filtration system was remarkably effective. The sand layers would trap particulates and some contaminants, while the clay lining prevented saltwater intrusion - a persistent threat in Venice’s lagoon environment. The result was surprisingly clean drinking water in a city where such a resource should have been scarce.

By the 16th century, Venice had developed over 6,000 such wells throughout the city. The Republic even established it’s own Ministry of Water in 1501, one of the world's first water management authorities, to maintain and protect these vital systems.

The wells weren't just engineering achievements - they were also works of art. The wellheads were often elaborately carved from Istrian stone, featuring everything from religious symbols to family crests. These decorative elements reflected Venice's dual nature as a city of practical merchants and ambitious artists, and embodied the massive wealth that the city was able to earn due to it’s independence.

While most of these wells no longer function as water sources (the city switched to modern water infrastructure in the 1800s), their design principles show parallels to contemporary challenges:

Sustainable water harvesting in water-stressed regions

Integration of infrastructure with public spaces

As water scarcity becomes a growing global concern, and humanity becomes more concentrated in urban areas, the ancient well system of Venice reminds us that innovative solutions often lie in understanding and working with local environmental conditions rather than fighting against them.

Appreciating historical infrastructure is important because it breaks many stereotypes we hold in our minds when we think or pre-modern people. While they may not have been as educated, people of the past faced and overcame many tough problems, without the benefit of modern tools or abundance. When considered against the constraints they faced, their solutions become elegant illustrations of human ingenuity, echoing through the ages.

-Connor, OfAllTrades

Very interesting. I recall reading about something similar in the deserts of India, a wide, gently sloping stone platform that funnels rainwater into an underground channel and carries it many miles.