What if everyone *did* just?

The secret sauce to understanding Japan

There is common wisdom passed around EA/Rat/TPOT circles that asserts that solutions that require coordination on the level of: “if everyone would just X” are inherently unworkable. Originating on tumblr (as far as I can tell), the saying has grown into a shorthanded rebuttal when proposed systems crumble to defection.

Japan however, seems to make a strong case that “everyone can just”, given a few preconditions. Instances where the Japanese coordinate on a level that would be impossible in other countries abound, but here are a few of my favorites:

1.) Old Enough!

This Japanese Reality TV show showcases the high degree of safety and autonomy afforded to Japanese children, who can safely cross roads, make purchases, navigate public transport, and much more, unaccompanied by an adult (save the camera crews). The full show is available on Netflix, and I recommend for any new parents.

This would be absolutely unthinkable in America and many other countries, where even leaving a child as old as 10 to walk a mile, can draw the ire of the authorities.

2.) Trash

Japan's approach to waste management demonstrates how internalized social responsibility creates effective systems without external enforcement. Despite the notable scarcity of public waste bins in major cities like Tokyo, the streets remain remarkably clean. This functions because Japanese citizens routinely clean their own shared spaces, and carry their garbage until they reach home or an appropriate disposal location.

I challenge you to take a moment the next time you step outside to start a timer, and end it as soon as you see any litter. My suspicion is that in the west, a 30 minute interval without a single sighting of litter is a luxury afforded only to the blind.

For those who do live in a pristine paradise and require an illustration, just take a look at New York City, where trash literally lining the streets and alleyways is a common occurrence. There are no norms here of taking care of your own trash, that duty falls on the sanitation workers, whose union has been notorious for holding the city hostage.

3.)Public Health

Even before the global pandemic prompted governments to spend billions on public health messaging campaigns, Japan had a remarkably strong culture of wearing masks when experiencing mild illness. In 2018, Japan produced or imported 5.5 billion masks, of which 4.3 billion were designated for personal use. That’s 34 masks per person per year, or around a 10% masking rate on average, assuming all masks are disposable.

This is a very common practice, and seen as a basic courtesy to protect others. This attitude extends to workplace culture too, where Japanese companies typically provide paid sick leave without requiring doctor's notes for short absences.

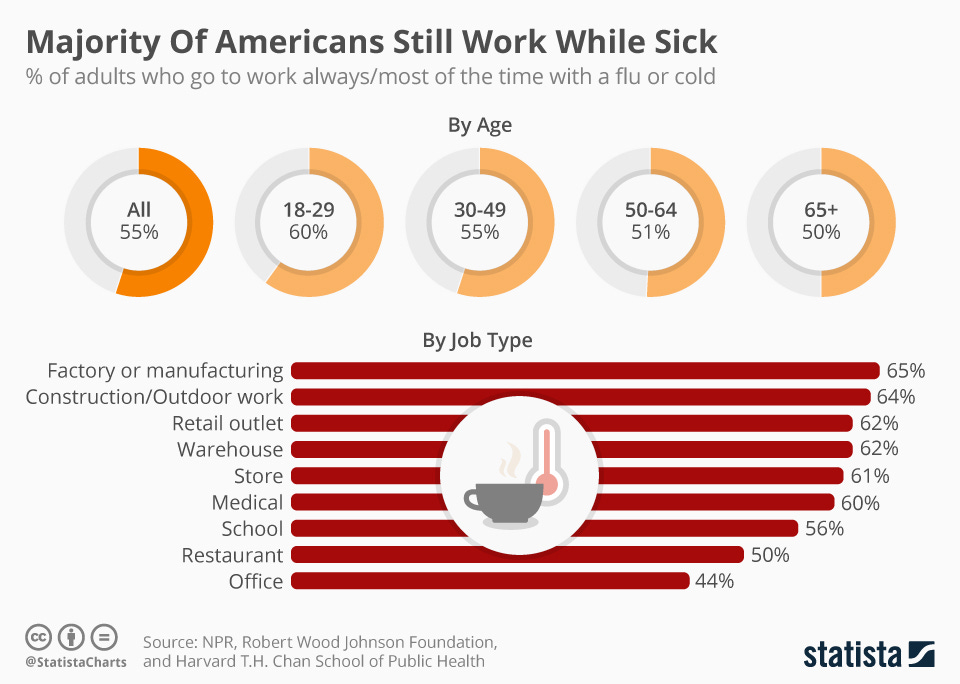

In contrast, many Western countries struggled to achieve widespread mask adoption even during peak pandemic media spending, and workplace cultures often incentivize employees to work while ill, with the strongest incentives for service sector employees. One study estimated that as much as 2.1% of all U.S. workers are working while sick in any given week.

4.) Institutional Trust

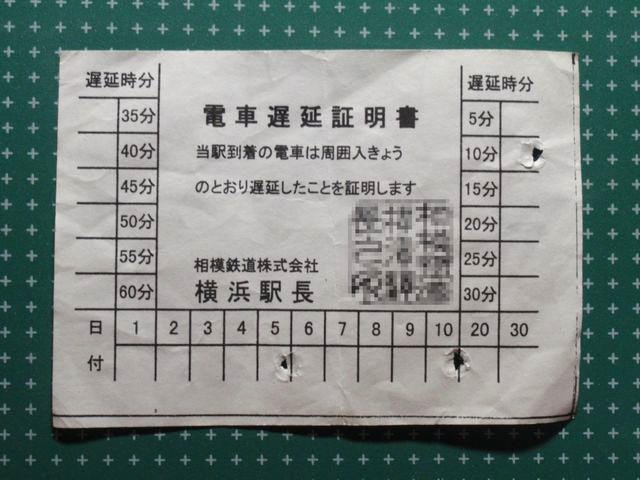

The Japanese railway system exemplifies how shared social expectations create extraordinary reliability. When trains experience delays exceeding five minutes, operators issue delay certificates ("chien shōmei-sho") that passengers can present to employers or schools.

The average delay on the Tokaido Shinkansen line is remarkably less than one minute per year. The shinkansen has an on-time performance record of more than 99%. Compare this to major Western transit systems - New York City's subway recorded an on-time performance of approximately 80% in recent years, while London's Underground achieves about 85%.

5.) Honor among thieves

Even within Japan's criminal organizations, the concept of structured social obligations persists. The Yakuza traditionally operated with explicit codes of conduct, including territorial boundaries, conflict resolution procedures, and obligations to local communities.

During natural disasters, some Yakuza groups have provided emergency supplies and assistance to affected areas. This differs markedly from Western organized crime groups, which typically operate with less structured codes and rarely maintain formalized relationships with legitimate society.

These examples establish a few important aspects of Japanese culture and society that explain their bewildering success in areas where almost everyone else fails, which I group together as “Legible Norm Conformity”.

Norms are shared by almost everyone

The norms that apply to a given situation are legible by most parties

Norms are adhered to by most parties

This is the secret sauce that allows children to safely roam the immaculate streets, business owners to provide legendarily good service on the honor system, and even criminal institutions like the Yakuza to exist largely in harmony with polite society. But why doesn’t this happen everywhere else?

Enter the World Value Survey. This graphic places countries on two axes, Traditional vs. Secular Values, and Survival vs. Self Expression Values, the definitions of which you can find at the W.V.S. For short, the top right corner represents very secular very individualist societies, and the bottom left corner represents very traditional, very conformist societies.

Japan is one of the few countries that is A.) Highly Secular, B.) Rich, and C.) Does not suffer from social defection. This mix is what allows them to continue to enjoy the bounties of safety, harmony, and trust we explored above, and break the rule of: “Everyone will not just”. However, let us not pretend that this comes without cost.

The Japanese deference to consensus and venerance for norms makes it a startup desert. Many would be founders leave the country to try their luck elsewhere. The ones who stay face a daunting bias of risk-aversion. The culture is so oppressive that by the account of writers like

You may be thinking: “surely foreign entrepreneurs are at the gates to fill this vacuum?” And you would be correct! They are at the gates, and Japan intends to keep them there. Although Japan puts on a friendly and welcoming face for tourists, they essentially disallow immigration compared to other G7 countries, and of the immigrant groups they do allow, a vast majority originate in countries that match the profile of Secular Conformity that Japan operates on.

Without the ability to maintain it’s shared and legible norms, Japan’s culture would cease it’s exceptional functionality. This creates a very narrow window in which Japan can have a pluralistic society. Perhaps this would all be well and good, save for the fact that Japanese birth rates are the lowest since 1947.

Shrinking by more than half a million people a year, the nation we know and love, (and it’s norms!) are almost certain to fade into an unrecognizable other.

This all paints a picture of Japan as a glorious but perhaps fleeting bubble of cultural functionality in a world largely dominated by more individualistic cultures. Whether or not this bubble can continue to survive, only time will tell, but I intend to book my tickets in 2025.

-Connor, Of All Trades.

I'm leaving Japan tomorrow having cycled around Kyushu for five weeks with my family. We have given the kids (2 and 4 years old) more independence than home (Australia) because of how safe it has felt. The lack of public bins has been difficult though, especially as we have nappies and are camping - sometimes carrying a few kilos of various types of rubbish. We've been through a bunch of the dying towns which has been interesting; sometimes we saw only 70+ year olds for a few days. While travelling I've reflected often on the things which could be possible if only people in my local area did just. Or more like *didn't* - nicer public parks and gardens, being able to leave a bike locked up with parts being stolen from it (in South Korea and Japan you can leave even luggage attached to an unlocked bike without fear of anything being stolen).

I suggest that there's a difference between "everyone just X" as an *input* to a plan/system/suggestion and "...and then everyone will X" as an *output* of a system.

Or, put another way, the most important word in "everyone won't just..." is 'just', not 'won't'. Japan didn't 'just' coordinate like that - they built their entire society from the ground up to achieve it, and it came with significant preconditions and consequences.

The correct understanding of the line is as a dismissal of any suggestion that tries to skip or ignore those preconditions and consequences, not as a dismissal of the whole idea of coordination. (This being the internet, I make no claim that people actually do understand it that way...)