Guilds: Past, Present, and Future

How understanding the guild model may help us build a better framework for institutions and policy as tools for progress.

Foreword

In this post I’ll be giving a crash course in the diverse history of guilds, their descendants that are still around today, and how the evolving model of the guild may be applied to our world in the future. The history of the guild model is important to understanding the contemporary institutions which continue to emulate the basic organizational structure of guilds today, and may play an important role in how we build better institutions and policy frameworks for progress.

A (Not so) Brief History Of The Guild

The diversity of guilds is assorted and colorful, but the gestalt idea of guilds reveals commonalities between these examples: A guild is an organization of voluntary members, with some level of exclusivity, that works together to accomplish a shared goal. With this general model of the guild in hand, let’s take a look at some examples throughout history.

Collegia

Some of the oldest well-documented examples of guilds date back to the ancient roman republic, as early as 100 BC. These guilds, called collegia, were essentially social and/or religious clubs which would coordinate collective action towards shared goals. Collegia dipped their fingers into a broad spectrum of pies, including lobbying and campaigning for pro-collegia candidates, performing cult religious rituals, both in secret and in public, performing community services and contributing to public works, and the conventional involvement in trade and specialized professions. These collegia often had to curry favor amongst the political classes to obtain an imperial sanction to operate, which was just a fancy roman way of saying license. As the political landscape in Rome shifted over the coming centuries, so too did the role collegia played, sometimes acting as private militias, or attempting to violently further their own political ends. Even in the last days of the empire, the landscape of collegia was diverse and varied, some including members who were slaves, while others were made up of a specific group of craftsmen, like the “College of Makers of Chairs for the Gods”, The system of collegia remained active in some form until the fall of the Byzantine empire in 1453.

Proto-guilds/”gilds”

The next guild-variant I’d like to highlight is the proto-guild. Also referred to as gilds, these were very simple styles of guild that predominantly existed in the early medieval period. These gilds are thought to be mostly Germanic in origin, and were much more loosely defined than the mid to late medieval crafts guilds that followed them, and that most people are familiar with. They were not centered around an occupation, and were largely geographic in nature. Gilds tended to have a founding goal, which could be anything: getting together every month to feast and drink, discussing religious philosophy behind closed doors, or providing policing services and protection from bandits for the local people and merchants. Interestingly, it seems that as long as you lived in the area the gild operated in, and could contribute something of value, just about anyone could join. Gilds in this period have been recorded as including serfs, religious figures, nobles, and even women.

Other notable guild-variants

The organizational structure of the guild is not exclusive to Europe. In fact, it’s thought that the first guilds may have arisen in ancient Mesopotamia, thousands of years before the roman collegia, called “ugla” in Sumerian, or “aklu” in Akkadian, these guilds mostly centered around the palace structure, and including specialized workers like brewers or smiths, overseen by a representative of the palace or temple they worked in, and were much less independent in their operation than our idea of guilds may imply.

Also of interest are the Za and Cohong of the far flung lands of Japan and China, respectively. The Za were a type of trade guild that began in the 11th century, which functioned as a way for participating merchants to collectively patronize temples and shrines, selling their goods there, and utilizing Japan’s network of shrines and temples as intermediary safe havens for traveling merchants wary of bandits and temperamental daimyo. When Oda Nobunaga established the parallel rakuza, or “free guilds”, the power and influence of the Za diminished greatly, beginning a period of gradual change, eventually giving way to the zaibatsu and keiretsu monopolies in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The Cohong arose as a result of the friction between the western trade companies and the late 17th and early 18th century Qing dynasty, and were the exclusive legal interface for trade between the two entities. They managed the Consoo Fund, which pooled tariff money to cover any debts of participating merchants, and pay bribes and tributes to the Qing bureaucrats. During the Opium wars, the Cohong became heavily entangled in the trade of opium, and growing richer as the power of the Qing government waned, largely ignored imperial edicts restricting western trade. The Cohong were officially dissolved as part of the Qing terms of surrender in the first opium war.

Guilds and the state

As we have seen, it’s relatively common for guilds to become a vehicle through which it’s members can collectively interact with the state. Whether this is in the form of obtaining occupational licensing, a state sanctioned monopoly, special treatment, or just plain old lobbying, the relationship between guilds and governments has the potential to be very complimentary.

Some notable examples of this socio-hierarchical symbiosis include the Saxon companion guilds such as the Stellinga, who would raise groups of men at arms to aid their king in times of war. Mercantile and crafts guilds often acted as springboards for members to become royal advisors and gain a place in a monarch’s court, who would often act as backchannels between the ruler and the burgher classes. This patronization of the guilds and other special interests was an important dynamic in almost all royal courts. Indeed, sometimes the government became so inundated by special interests that it was as if they were really the one’s making the decisions, something we might call plutocracy.

However, guilds were not always in lock-step coordination with the state. Often times, they directly opposed the state, or even acted as substitute institutions, arising in the places that government was unable to reach. This competition to provide public goods was not always welcomed by the state.

Priest’s guilds were often seen as conspiratorial in the Carolingian world, and were legislated heavily against in the seventh and eight centuries. Higher ranking members of the church often became wary of these clerical guilds, and having the ear of local rulers, may have driven this paranoia into them in an attempt to cut their competition for power within the hierarchy of the catholic church down to size. Hincmar, archbishop of Reims in in the mid-to-late ninth century cracked down on these ecclesiastical guilds after priests were caught “attending raucous parties, either alone or with laymen, where they drank to the saints or to their own souls, got into fights and told stories to rowdy applause; others indulged in entertainments involving bears and dancing girls, or even demonic masks”. However, this account is almost certainly biased, and the real reason the archbishop cracked down on these guilds probably has something to do with the environment of free discourse, change, and growing rumblings for reform amongst the lower clergy.

A pertinent example of guilds as competition to the state is the protection guilds (also known as Frith guilds); whose purpose was to provide safety from bandits and thieves in a certain area. Sometimes these guilds were welcomed as complementary to a state that could not protect it’s people, such as the peace guilds of tenth century London. Other times, these guilds were crushed by state armies who felt their existence threatened the absolute nature of governmental power. In late 9th century France, King Odo famously slaughtered members of a protection guild for daring to swear oaths to each other, which was seen as insubordination to their loyalty to him. Protection guilds are a great example of how a private institution might provide public goods when government is absent from the environment. This is part of why exclusivity and binding, costly rituals such as the membership oath seen above were so important. They helped guilds eliminate free riders and operate efficiently to provide public goods in areas where governments could not do so.

One interesting fusion of guild and state is the ideology of “guild socialism”, which advocated for the workers of specific industries to band together (usually within national borders) to set wage floors and control each industry in the collective name of that industry’s workforce.

It’s important to remember that guilds manipulated their regulatory environments not only by the carrot, but also by the stick, a ruler or government which pleased powerful guild lobbies could expect financial support in times of crisis, and even levies in times of war, while guilds who found themselves under restrictions too tight to be comfortable might sponsor a rival claimant to the throne or candidate in the election in the hopes of currying favor. This contributed greatly to the nature of the guild-government relationship, where a wise head of state would pit special interests against one another in order to prevent them from chafing under their own taxes.

Guilds w/o the state

Neither guilds nor the state need the other to exist. Often times, guilds filled the vacuum when and where governments could not. One pertinent example is the Lex Mercatoria, which was a collection of laws governing trade and merchant relations between nations, supercedeing national laws, and enforced by merchant courts. This set of laws was unique because it was produced and enforced voluntarily. These laws emphasized equality across borders, contractual freedom, and property rights. This system of guild law allowed merchants to confidently trade, even with people they were unfamiliar with, under terms that were commonly known to all parties. The Lex Mercatoria is an inspiration for our modern system of private arbitration courts.

There were also guilds that existed specifically to oppose the state, and provide black markets, and organizational infrastructure to those on the wrong side of the law. Examples include thieves guilds, some of more mythical or unconfirmable nature made famous by the 1455 Trial of the Coquillards in France, the secret society of the Garduna in Spain, as well as the more well known Japanese yakuza, and the Chinese triads (video link in footnotes).

Some guilds power grew to such heights that they became states in and of themselves, like the Hanseatic League, which formed from a guild that aimed to provide protection and facilitate trade in northern European cities and towns in the late 12th century, and grew into a loose confederation of states by the end of the 13th century, stretching from the Netherlands to Russia.

Guilds today

Guilds and their descendants still play large roles in our modern society. I was a member of two fraternities in college, and they fit the definition of a guild. They are built around the exclusivity of their social networks, common resources (like a fraternity house or party fund), special privileges afforded to them by collective bargaining with the university, and the status that comes with association. These goods are kept exclusive by the member induction process, where the ingroup imposes relatively tight boundaries in order to eliminate free riders.

I’m also lucky enough to be a member of a labor guild, and have the value of my work as an engineer inflated in part by the professional licensing apparatus of interest groups like the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying and the American Society of Civil Engineers (these guys played a big part in making the infrastructure bill so big, they put out the “Report Card For America’s Infrastructure” every four years). This also has a secondary status effect because they keep incompetent people and bad actors out of the field, lending engineers who do qualify for licensure much more trust from the public.

Some of my readers may be members of unions, which operate very similarly, often lobbying employers or local governments for special protections in order to advantage their members over non-union workers and raise wages within the union by using exclusionary tactics to monopolize a labor pool. You can read more about this theory of unions here.

Guilds online

Similar to thieves guilds, in hacker circles, there are private and clandestine guilds that control access to secret marketplaces such as DARKODE; a darknet hacker guild where stolen information, specialized malware, and botnets can all be bought and sold, as well as a message forum where members can connect, socialize with, or seek advice from other hackers.

While DARKODE may be a virtual extension of our “real” world, even in completely virtual worlds, people organize into guilds in order to build institutions that represent their interests. Some notable examples include the guilds of Eve Online, called “Corporations” in game, where players organize to buy shared equipment, have a safe internal marketplace for trade, or fight other corps in large scale fleet values over trading monopolies. The scale of these battles is stupendous, with the largest ever in late 2020, known as “The Massacre at M2-XFE” costing players in EVE’s largest two guilds 380,000 USD. (The account of the battle reads like something out of the Pacific Theatre in WW2, it’s seriously awesome).

So it’s clear from the graph above that even virtual guilds can reach back into the real world via game mechanics, like in the case of EVE. But what about virtual guilds affecting their own virtual worlds via real life mechanics?

Interestingly, this has happened too. Allow me to introduce Foxhole.

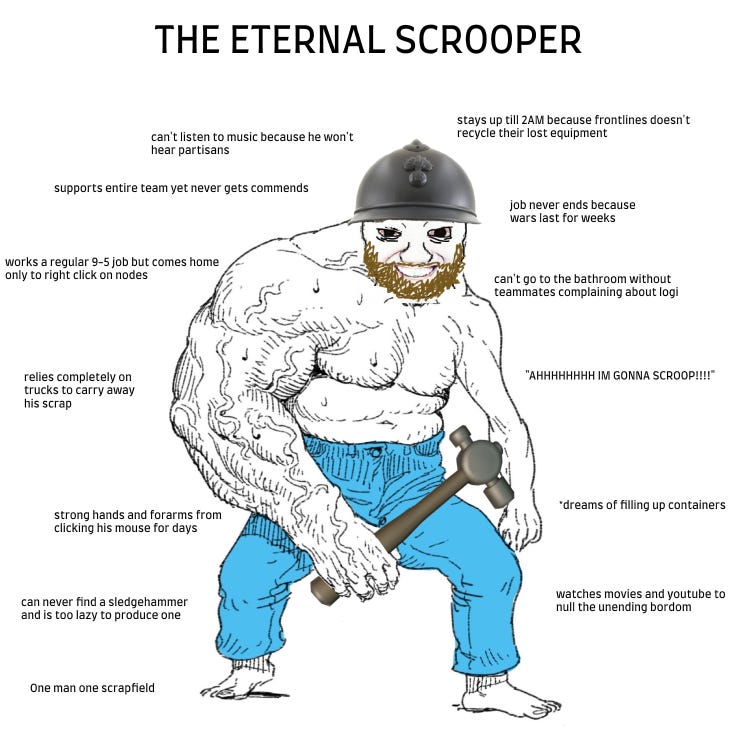

Foxhole is a large scale faction-on-faction war game where players not only have to fight on the frontlines, but also produce and truck supplies to and from the front in real time to supply any fighting actions. This means that in Foxhole, every tank, rifle, bomb, plane, truck, etc. has a real life player behind it. This divided each of the game’s factions (called Wardens and Colonials) into two types of specialized players, the fighters and the logistics players. The much more fun game loop of fighting was totally dependent on real players producing things in the logistics or “logi” play-loop, which mainly consists of scrapping for materials (called “scrooping” in game due to the in game censorship of the word crap), and manually transporting those materials to the front.

Logi players on both sides of the game’s faction war got fed up with how boring and repetitive their game experience was, and in early January of 2022, the logistics players formed a guild across the war lines to coordinate an in-game strike in a bid to get the attention of the almighty devs to change the logi playloop to be more fun. They wrote an open letter to the devs, translated into more than 14 languages, and signed by 2000+ players which you can find here. The movement also spawned memes expressing their dissatisfaction at the logi gameplay experience such as the one below.

Some players even went so far as to play the frontline game loop in ways that destroyed enemy equipment rather than just not produce any, in order to starve the frontline game loop of both sides. Within hours, frontline players who had previously been able to engage in fun activities like airstrikes, tank battles, and artillery barrages, were so starved of supply that players had to fight each other using only their pistols. After their 49 day strike, their demands were met, and the game was vastly improved. If you think of their virtual world as analogous to our real world, this guild literally lobbied their God for changes to be made, and won.

Guilds in the future

I’m no Nate Silver, but in the future I think we will likely see a return to the guild model, on a scale much more similar to that of the Hanseatic League, especially online and in virtual worlds, in environments where conventional organizations built on geographical proximity and the ability to enforce rules with violence diminishes. In the next 50 years, I hope to see the model of voluntary but exclusive group formation expand and grow. With the incumbency of Charter Cities, Seasteads, and the Network State, I think there is much to come and high progress returns to understanding the nature and history of the guild model.

Conclusion

The storied history of guilds serves as a great tool to give context to some of our most important contemporary institutions. If you can come to understand the basic organizational model of the guild as a voluntary but exclusive group with shared membership benefits, capable of providing public goods in environments where governments fail to do so, you can extend that to many unique domains, and use it to accomplish the goals you share with others, whether they be your next-door neighbor or a fellow player from the other side of the world.

Rather than think of guilds as an antiquated relic of a time long ago, we should look to examples like the Network State, Charter Cities, Hacker Guilds, and guilds in virtual worlds for guidance as to how the guild may become more important in our future as a framework for institutional progress and policy change than it ever was in our past.

-Connor, OfAllTrades.

Like this article? Please Subscribe!

Know someone else who would? Share with a friend!

And if any of you readers out there are secretly crypto millionaires and would like to leave a tip, please check out https://alltrades.eth.xyz/

Extras

Further Reading:

Guilds, states, and societies in the Middle Ages

A history of British Trade Unionism

Work, Labour, and Professions in the Roman World

Restoration of the Gild System

Related Videos:

Foundation of Medieval Guilds

(Seriously, this one is great)

“dipped their fingers into a broad spectrum of pies”

this was strangely appetizing

Have you been able to put much thought into the history/future of “civil society guilds” a la the masons, lions, elks, etc. given their significant decline over the past half century plus? (Have a self interest in answers to this question, as a mason myself).